When two Miami University students were rumored to have COVID-19 last January, junior American studies and film major Jack Lichtenstein didn’t panic.

“If I’m gonna skip class, it’s not going to be because of this,” he told The Miami Student last year.

Unfortunately, the pandemic had different plans.

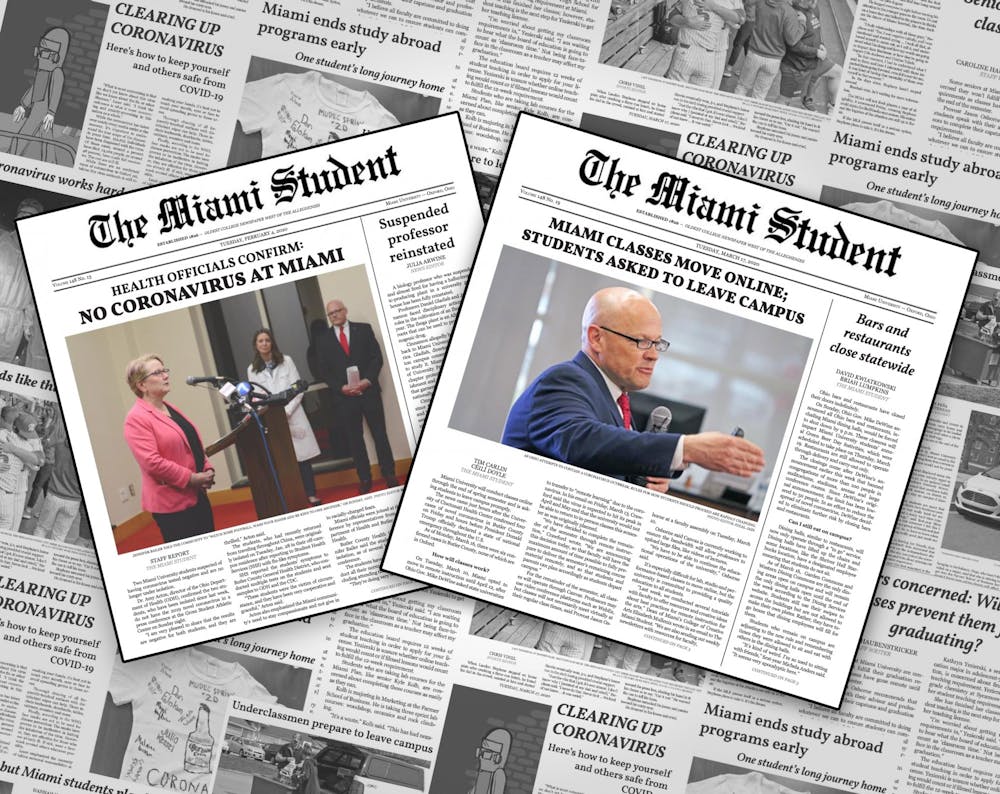

Miami was one of the first universities in the country to have a COVID-19 scare, on Jan. 28 of last year. At the time, there were only 4,500 cases worldwide. The New York Times wouldn’t begin tracking the outbreak in the U.S. for another month.

Before the two Miami students could be cleared, their tests had to be sent to the CDC lab in Atlanta. Amy Acton, now former director of Ohio’s Department of Health, held a press conference in Oxford to calm the community.

It took six days to get the results — negative.

Today, students can walk to Harris Hall, take a rapid test and get their results within a half-hour. And as the world enters 2021, the U.S. sits at more than 25 million COVID-19 cases and 436,000 deaths with a new strain of the virus being found throughout the country despite the creation and distribution of a vaccine.

Reflecting on the past year, Lichtenstein said he knew the pandemic would be bad but had no idea of the scale.

“Back then, I would’ve thought that we’d have gone home [the spring semester] and gone back [in the fall],” Lichtenstein said, “that by the time the next semester rolled around everything would be back to normal. I just didn’t expect a total failure of the healthcare system like we saw.”

Forty-six days before President Trump declared COVID-19 a national emergency, Miami became the first university in the country to cancel athletic events due to the virus. The men’s basketball team was supposed to play Central Michigan on Jan. 28, the day Miami reported two potential positive cases.

David Sayler, Miami’s athletic director, said the opposing team was already at Miami when the decision was made to postpone the game.

“The other athletic director and I had a discussion over the phone,” Sayler said. “I informed him of the potential cases and what we were doing about it. We agreed to have a discussion with our administrators about whether we felt we should move forward or not, and by the time I had talked to ours here, they had taken their kids off the floor and left.”

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

The next day, the women’s basketball team postponed a game against Western Michigan. With no results from the CDC yet, Sayler said the other teams were unwilling to play against Miami.

University administrators worked closely with the Ohio Department of Health and the CDC to handle the first suspected cases. As COVID-19 spread across the nation, the response had to become more localized, and the university now relies on guidance from the Butler County Health Department.

For Dean of Students Kimberly Moore, those first unconfirmed cases established partnership as the focus of the Oxford community’s response over the next year.

“What [the first scare] was most helpful with was establishing relationships and lines of communication,” Moore said. “We learned a lot about what we didn’t know and what we needed to know quickly. At that time, it was like, ‘We need to really focus and get things under control for a couple months.’ Nobody at that time ever imagined we would still be in this a year later.”

This partnership proved its importance as cases jumped from the end of January to March resulting in Ohio State University announcing on March 12 that classes would remain online for the rest of the semester. The following day, Miami followed suit.

Lichtenstein and his classmates weren’t too concerned.

“I was in a documentary class … when we found out we were getting sent home,” Lichtenstein said. “We all got super excited. No one was wearing masks at the time; we weren’t even thinking of it. Everyone was out that night. [Brick] was jam packed – there was a line to get in. It was insane. Everyone got out of class and just went to the bar.”

By the fall semester, Liechtenstein’s outlook had changed. He opted to remain online rather than come back to campus and is doing so again this semester.

Things aren’t yet back to normal for Sayler, either, though he said not every change brought on by the pandemic has been for the worse. He now has weekly meetings with other athletic directors in the Mid-American Conference and gets to see more student athletes over Zoom than he would normally interact with.

“I think the more constant communication among schools is a good thing,” Sayler said, “and we’d like to be able to continue some of those conversations. I think the more face-to-face time with more student athletes is a positive that I’d like to continue ... We’ve been able to improve our communication and have it be more accessible to more people in a better way, and that’s the kind of thing I hope will continue even after this is in our rearview mirror.”

Looking back, Moore said she is proud of the work the community has done, even though the pandemic has been a longer struggle than anyone anticipated.

“We didn’t get it perfect — certainly not,” Moore said. “We wouldn’t claim to. We definitely had to get better and learn week to week, but I am really proud of the work, and the cross-divisional partnerships and collaborations have been incredible … I didn’t sign up to be in public health. I’m an educator. But given that these have been the circumstances, I am proud of where we are.”