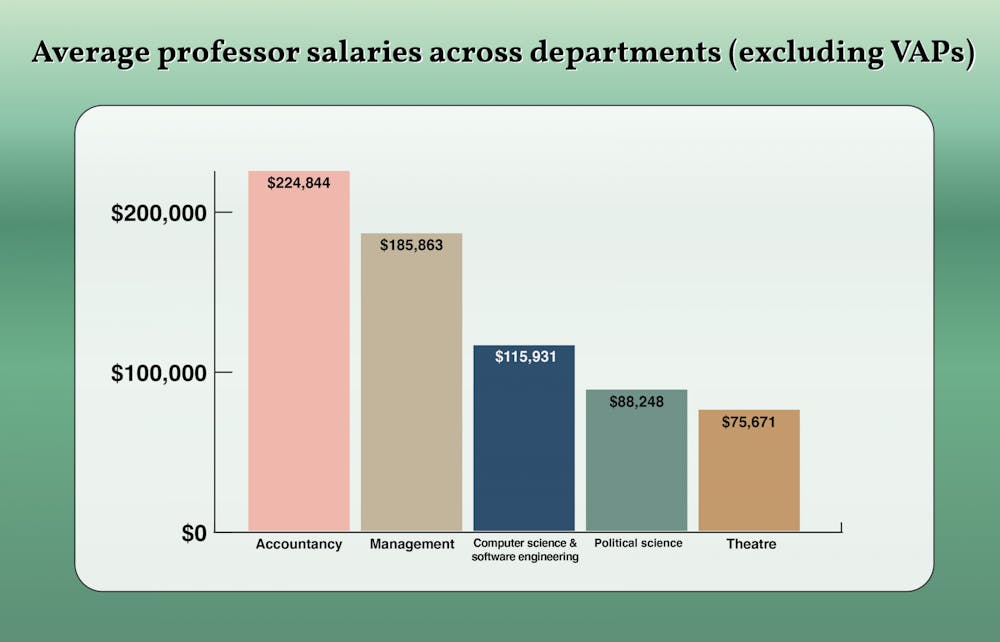

Associate, assistant and full professors in Miami University’s Department of Theatre pulled an average salary of just more than $75,000 in 2019.

For accountancy professors, the average was just shy of $225,000.

Data compiled by The Buckeye Institute, which publishes salary data for public universities in Ohio, reveals a stark disparity in faculty compensation across Miami’s academic divisions. Of the 62 professors – excluding deans and associate deans – who made more than $200,000 in 2019, more than 50 taught in the Farmer School of Business (FSB).

But David Creamer, senior vice president for finance and business services, said the gap in salaries isn’t unique to Miami. The university has to compete with private sector jobs to attract talent, and the market varies across different fields of expertise.

“In disciplines like engineering, computer science, business, they tend to be the individuals as much in demand in the private sector as they may be within higher education,” Creamer said. “Some other disciplines are primarily being employed in higher education, and it's a matter of what the market is suggesting about their compensation.”

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that computer scientists across all sectors make an average of $96,770 per year, with the highest earners making more than $135,000 in transportation and manufacturing. By comparison, Miami’s computer science and software engineering faculty average is just less than $116,000.

In addition to private sector opportunities, faculty salaries take into account the additional responsibilities professors take on.

Most faculty are hired on basic 9-month contracts, and when they teach over the summer or during J-Term, their salary increases. Other factors include administrative positions like department chairs and leading experiential learning opportunities like study abroad programs or research.

Some faculty positions come with built-in endowments from private donors. FSB has endowment contribution tiers that determine which positions carry the donors’ names. A $2 million contribution gets a chair position, while a donation of $300,000 goes toward the salary and related research of a specific professorship like the “PricewaterhouseCoopers Professor of Accountancy” position.

“There’s something that makes [endowed positions] unique,” Creamer said. “You're trying to recruit … somebody to that position that has national ranking. As a result, to compete for that type of position, the pay tends to be much higher and may be more aligned with what some of the executive compensation looks like.”

Melissa Thomasson, associate dean of faculty affairs and personnel in FSB, wrote in an email to The Miami Student that the college has 32 faculty with named professorships which help the school remain a competitive hirer.

She wrote that it’s especially important for FSB to offer competitive salaries for professors in fields like accounting where there are few PhD programs nationally.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

“Compounding the problem for some departments, like accountancy, is that there are not a lot of schools that train PhDs,” Thomasson wrote. “As a result, many universities compete for a scarce resource. This drives wages up.”

For Cameron Tiefenthaler, a sophomore double majoring in political science and human capital management and leadership, the difference in compensation isn’t surprising. Like all business majors, she pays a $100 per credit hour surcharge for each FSB class.

“People will jokingly say like, ‘Oh, what’s it for?’” Tiefenthaler said. “ … I have heard some people say that, ‘Oh, we have to make sure that the professors are paid a competitive wage, especially in the business school.’”

Tiefenthaler’s management professors in FSB have an average salary of more than $185,000, more than double that of political science professors in the College of Arts and Sciences (CAS), who average just more than $88,000.

Provost Jason Osborne said the university has little control over what fair salaries across departments look like.

“We're not creating or dictating the market,” Osborne said. “We're responding to the market because we're trying to compete with other institutions for the best faculty we can get.”

Osborne said the university relies on state and national data compiled by the College and University Professional Association to keep faculty pay competitive.

Across national institutions, for example, full professors of business average $118,000. Nationally, assistant to full English professors make between $60,000 and $86,000, while Miami faculty in English average more than $87,000.

“If we're out of alignment with the market, we're either going to pay way too much, or we're not going to get anybody,” Osborne said. “So we pay close attention.”

Tiefenthaler said unless market pressures change, there’s little chance of a decreasing wage gap across departments at Miami.

“As a society, we don't place enough value on arts … No one's going to justify realistically paying a painting instructor $200,000,” Tiefenthaler said. “That's just the way it is. So, in order to fix that … society would first have to put a greater emphasis on the importance of those areas.”