Miami University’s preppy reputation is no secret to anyone, but financial and anecdotal evidence shows that sentiment has contributed to a lasting impact on the university’s socioeconomic diversity.

While federal privacy laws protecting students’ financial disclosures make it difficult to understand how many low-income students are admitted to a university, one indication is through the percentage of students receiving a Pell Grant.

This federal grant is available for students who display a high need for financial aid. The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) compiles Pell Grant statistics for colleges across the country.

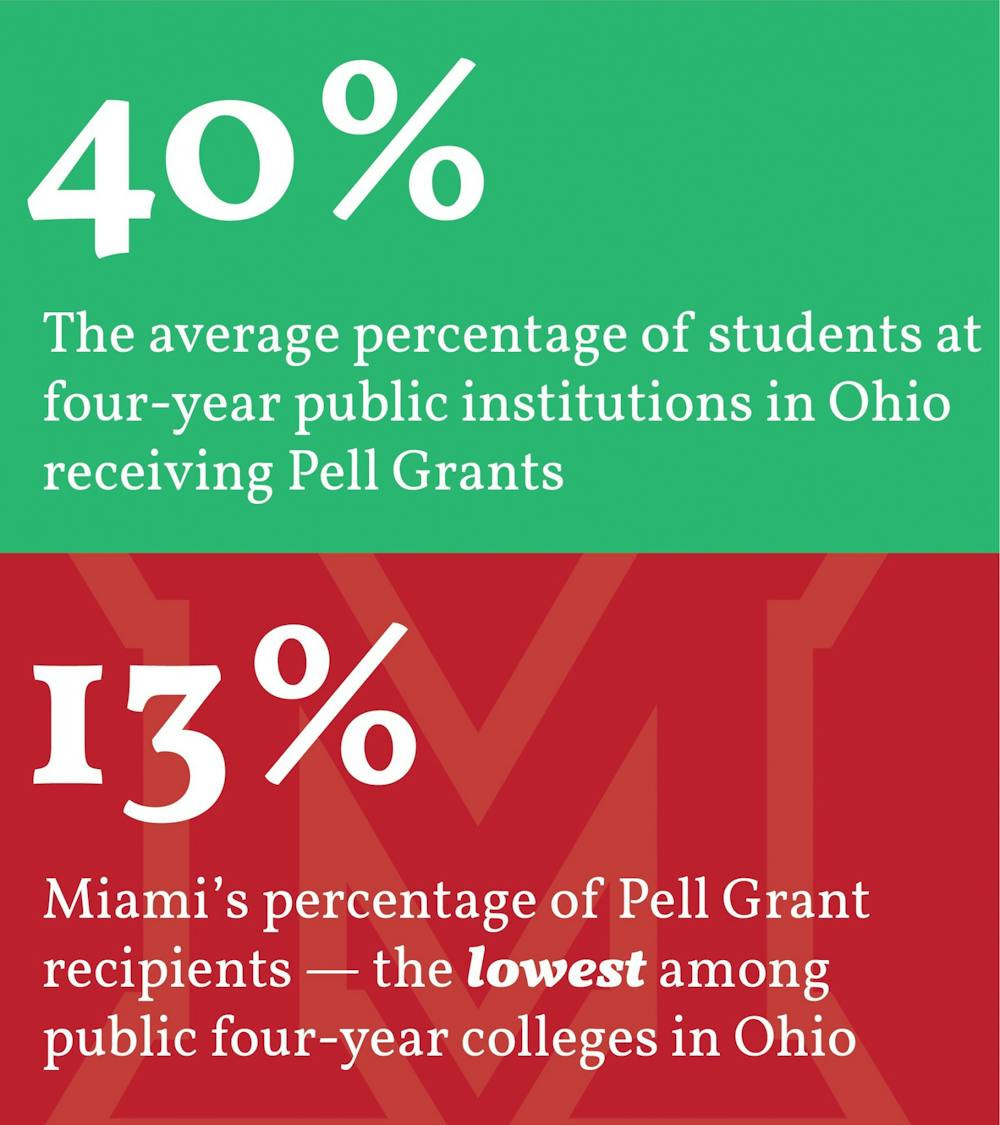

NCES found that 13% of Miami students admitted in the 2018-2019 school year received Pell Grants – the lowest among four-year public universities in Ohio.

For comparison, the average percentage of students receiving Pell Grants from four-year public universities in the state is 40%.

Beth Johnson, the director of student financial assistance at Miami, wrote in an email to The Miami Student that admission decisions are not affected by a student’s financial circumstances.

“Admission decisions are based on a review of the student’s admission materials and are NOT [sic] based on financial data,” Johnson wrote. “Admission decisions are need-blind.”

First-year Lexi Fields, an integrated social studies education major, received a Pell Grant after being admitted to Miami. She said she notices some members of the student body have a different outlook when it comes to finances.

“I can definitely tell that [money] just doesn't really cross their mind the same way that it does for me,” Fields said. “It's kind of the same with tuition, maybe we were talking about getting our books or how many courses are taking. For some people, they just don't even really recognize or realize that funding is a struggle for some people.”

Despite the limitations placed on publicizing financial information, a 2017 New York Times study gave some indication of Miami’s socioeconomic diversity.

According to the study, the median income of families of students at Miami University for the class of 2013 was about $119,000 a year. In comparison, the median income of households in Ohio is just more than $48,000 according to 2013 U.S. census data.

First-year business economics major Evan Gates, who posted The Times study to his Instagram, said the date of the study’s publication does not necessarily change its relevance.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

“We don't have more recent numbers that you can go find anywhere,” Gates said. “I think that points to the reality that [today’s demographics are] probably pretty similar to what we saw [in The Times study].”

The study, based on millions of anonymous tax records, “shows that some colleges are even more economically segregated than previously understood, while others are associated with income mobility.” It estimated how Miami compares with its peer schools in both economic diversity and student outcomes.

Miami ranked third out of 377 “selective public schools” for the highest percentage of students coming from the top 1% of the income distribution. According to the study, about 7% of Miami students’ families make $630,000 or more annually.

Miami senior and Student Body President Jannie Kamara said she was disappointed to see the number of students from the bottom 20% of the study’s income distribution.

Just less than 5% of students came from these families, who make $20,000 or less per year.

“I think as an institution we focus a lot on so many other areas of diversity and inclusion, that we don't talk about class,” Kamara said. “And that's a very big issue here on campus that we do need to have a complex conversation about.”

Jonika Moore, senior associate director of admissions, oversees diversity initiatives and recruitment at Miami. She said the data presented in The Times study doesn’t necessarily reflect everyone at Miami.

“Even though I would have been considered in the bottom 20% back in my day, I wouldn't have been in this data because my mom did not file taxes,” Moore said. “She was on public assistance.”

Moore said she isn’t able to confirm the information because federal privacy law prevents the sharing of students’ income data.

While she’s unclear on how accurate The Times’ data is, Moore acknowledged that it shows there is still room for improvement when it comes to Miami’s socioeconomic diversity.

“I do believe Miami has work to do in this area because I think that — not because we don't recruit students — but we also have the issue of perception,” Moore said.

Moore said before potential students even apply to Miami, they may be hesitant to give the university a chance.

“Sometimes, the perception of Miami hinders students from choosing Miami,” Moore said. “So they’ll assume, ‘Well, everybody is rich there, so I'm not going there,’ when that's not accurate.”

Fields said she knew of Miami’s reputation when she applied to the university.

“I knew coming in that Miami stereotypically was kind of a party school, rich daddy, coming from a rich background,” Fields said. “And I just was never really that. I definitely don't come from that rich background that the stereotype kind of calls for.”

Kamara said students might not just be deterred by Miami’s reputation — they may be more concerned with Miami’s price tag.

“Many people look at Miami’s tuition and are deterred to go here because it's so expensive,” Kamara said. “A lot of students come here who are at lower income because of scholarships, and I think that shouldn't be a student's main proponent for coming here.”

Gates said this was something he experienced first-hand as an out-of-state student. Before scholarships and financial aid, he could have been paying more than $51,000 annually to attend Miami.

According to College Tuition Compare, Miami has the highest out-of-state tuition of all public universities in Ohio. Its in-state tuition is the sixth highest of public universities in the state.

“That's a sad thing to say, money is a big thing when we're looking at colleges,” Kamara said. “We should really look at, as an institution, how we reduce tuition ... because at the end of the day, we’re also looking at how we ensure that students are having low student loans as they're leaving college.”

Moore said funding college is much different today than it was when she was a student at Miami. The state and federal government give less aid to students than they have in the past, leaving it up to universities to fund the majority of scholarships.

“[Miami is] tuition driven,” Moore said. “The money has to be raised. So we can only give you what we have. So at some point, it's kind of like there's a cut off on how many full-ride students we can support. If you're in the bottom 20 [percent], that means Miami has to cover the whole thing.”

But even with limitations on the amount of full-rides that can be given out, Moore said Miami does “very well in scholarships.”

“We don't make our students have to jump through a bunch of hoops to give them the money,” Moore said. “We kind of give you all your money. If you fill out the FAFSA and do the application, we give you all the scholarship money that we're going to give you.”

Fields said her experience with One Stop, Miami’s financial office, has been a positive one.

“The university and other people that are helping us with financial aid – people in the One Stop – I think they really do care about us and want to make sure that we have the financial means to get through college and pursue our dreams,” Fields said.

In her position in the admissions office, Moore said she works to make sure potential students are aware of opportunities for them if they apply. One of the ways she does that is through the Bridges Program.

The program website invites students of underrepresented populations to apply. Students who are accepted into the program will be brought to campus to attend different lectures, including one centered around diversity. Participants then spend the night in Miami’s residence halls before leaving the next morning.

“We're able to encourage students to at least participate in the program to make an informed choice,” Moore said. “You can still decide that Miami's not for you, but at least you're making it from an informed perspective, as opposed to what you believe what Miami is.”

Moore said 97% of students who attend Bridges and apply to Miami are admitted, and almost half attend.

Sophomore mechanical engineering major Alex Hauptman participated in the Bridges Program in high school. Now, as a student at Miami, Hauptman helps with the program when needed.

“I think that one of the very strong messages is that no matter who you are and what background you come from, everyone has a very unique story,” Hauptman said.

Junior speech pathology major Sunita Dhar also did Bridges in high school. She said she doesn’t think the program is representative of Miami’s diversity on campus, but she expected that.

“I don't feel like that it’s bad in any way because it misrepresents,” Dhar said. “I just think it's a program for students that are of color or are diverse. It's just kind of all of those people in one place.”

Dhar said in her hometown of Toledo, Ohio, Miami had a reputation for being a school for wealthy white families.

“I definitely didn't think it was as white as it is, because in college pamphlets, I feel like they always try to sneak in some color somewhere, so it looks like everyone's represented,” Dhar said. “I mean, I knew that it was a pretty rich, white school. I didn't think it was as rich and white as it is, but I wasn't shocked or anything.”

Currently, Bridges hosts four sessions with 150 students per session. Moore said she would like to do more sessions to accommodate the many more students who are applying to the program, but there isn’t enough room in the budget.

Once students are admitted to Miami, Moore said the Student Success Center (SSC) can also provide low-income students with resources they may need.

Craig Bennett, senior director of SSC, said Miami offers programs that connect students experiencing homelessness with temporary housing, students with food insecurity with the swipe donation program and students in technological need with the F5 laptop program for a refurbished laptop.

When the COVID-19 pandemic began, Miami created the Emergency Needs Fund to help students in need. As of Feb. 5, the fund raised more than a million dollars from more than 2,000 donors. The fund is still open today.

“I think our alums and corporations are really stepping up to help fund us,” Bennett said. “And it's making a huge difference with students.”

While Miami’s number of Pell Grant recipients is lower than other schools in the area, Johnson said students who come to Miami are more likely to succeed.

“Pell Grant recipients graduate from Miami at a higher rate than most Ohio public universities,” Johnson wrote. “Of Miami’s spring 2018 graduates from the Oxford campus who received Pell Grants, 96.8% of them either secured a job or were continuing their education by the end of the year.”

Moore said as a low-income Miami graduate herself, her story isn’t unique. She said she believes other low-income students can succeed at Miami.

“If you come to Miami, you study at Miami, you engage … there will be increases in outcomes,” Moore said.

Kamara said she is looking forward to having a more complex conversation about socioeconomic diversity on Miami’s campus.

“I’d like to see – as an institution – how we can better talk about class,” Kamara said, “and how we can better break down ideas of class to help push a better class consciousness, because there are students of lower income.”

Fields said she hopes the student body will begin having a conversation of their own.

“I think we just need to acknowledge and realize our differences,” Fields said, “and just talk about it more openly instead of it just kind of being a taboo thing.”