Throughout history, many black students have experienced racial discrimination during their time on Miami University’s campus.

From people wearing blackface at fraternity parties to white students pretending to be stereotypically black to racist rhetoric in group chats, black students have seen their fair share of injustice.

Yet, with each uprising of hatred, black students have banded together. In 1998, black students formed the original Black Action Movement (BAM), seeking to eradicate Miami’s racist culture. And again, in spring 2018, black students established BAM 2.0 to stand up for equality for themselves and other students of color on Miami’s campus.

Since the era of Nellie Craig, the first black graduate at Miami in 1903, black students have been fighting for equality while also making history.

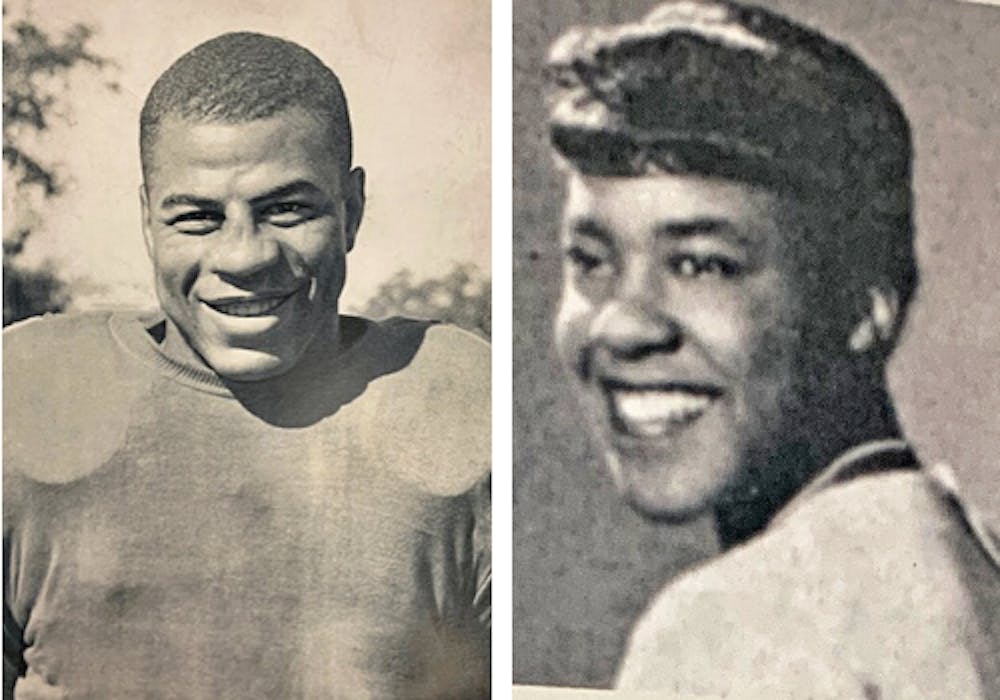

Jerry Williams ’39 and Myldred Boston Howell ’49, two of Miami’s earliest black students, are no exception.

Though they faced many obstacles, both prevailed and created a lasting impact on the Miami community.

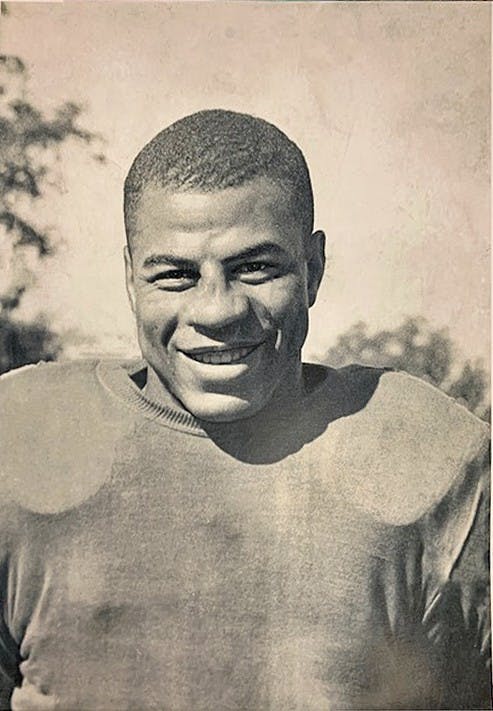

Jerry Williams ’39

Jerome “Jerry” Williams was born in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1915. As a teenager growing up in Cleveland, he exhibited incredible athletic ability in football and track. As a high schooler, he was a member of his school’s championship relay team that was anchored by Olympic all-star athlete, Jesse Owens.

Williams’ athletic accomplishments continued in college as he became a two-star athlete in football and track and the first African American in Miami’s history to compete in varsity sports. In his sophomore year, he earned a spot on the football team as a half-back and led his team to the Buckeye Conference championship.

His senior year, he also made history by becoming one of the first black students to compete against a segregated school on Miami’s home field. Williams was also a championship boxer, winning the southwestern Ohio divisional Golden Gloves in back to back years.

Williams has gone down in history as one of Miami’s greatest athletes. But his time as a Miami student did not mirror his athletic achievements.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

Williams, and the other 12 African Americans who attended Miami at the same time, could not live on campus because of Miami’s long-standing policy preventing it, according to “Miami University 1809-2009: Bicentennial Perspectives,” written by professor of history and American studies and former director of the William Holmes McGuffey Museum Curtis W. Ellison.

Despite his accomplishments on the field, Williams was put to the ultimate test academically. He was a relatively good student, maintaining a “B” average throughout his college years. As a physical education major, Williams completed all of his major’s requirements to graduate except the student teaching component.

As a black man in Butler County, Williams couldn’t student teach in local schools due to discrimination. The administration did not assist him in finding proper placement elsewhere. Because he was unable to fulfill this requirement, Williams could not get a bachelor’s degree from Miami. He later went on to teach for a year at Cleveland City Schools.

Seth Seward, assistant director of alumni relations, runs the “mublkalum” page on Instagram which highlights Miami’s Black Alumni. During Black History Month, Seward has dedicated the page to highlighting alumni like Williams and the struggles they’ve faced.

“This man proved that he was just as intelligent [as] anybody else and could do the coursework,” Seward said. “It just happened to be because of the color of his skin that he was discriminated against.”

“I’m just glad to be able to be connected to him,” Seward added. “He was here. He was in similar classrooms. He was walking the same streets as us. And there's just a history that kind of grabs hold on to you and keeps motivating you every day to do well.”

After leaving Miami, Williams went back to Cleveland, his hometown. There, he was hired as a physical education coach through Cleveland City Schools. But he was fired after his first year because he still lacked a teaching license after Miami refused to count his year of work into his student teaching requirement.

City Schools petitioned the university to credit his year of teaching in Cleveland to count toward a teaching license, but Miami rejected their request.

It seemed as though Williams’ story was over until 2013, when Honors Program Director Zeb Baker found some more information in Miami’s archives. Correspondence between former university president Alfred P. Upham and Cleveland City Schools superintendent Charles H. Lake shows Upham admitting that Williams had essentially completed all of his requirements.

Baker then presented the evidence to Dr. Ron Scott, Associate Vice President of Institutional Diversity, who advocated that Williams should receive his bachelor’s degree posthumously among senior administration.

After verifying Williams’ registrar multiple times, Michael Dantley, dean of the College of Education, Health and Society, gave Janis Williams, Jerry’s daughter, a phone call — her father was finally going to receive his degree.

“Wow, you finally got it,” Janis Williams said in an interview with the university after she and her brother Jerry Jr. accepted their father’s degree. “You finally got it. And you deserved it.”

Jacqueline Johnson, current university archivist, assisted Baker in finding the information about Williams. She said Williams’ ability to send his children to the same school where he faced hardships is incredible.

“You spend four years of your life at a university,” Johnson said. “You were up and down the field [playing] football. [You were] a multi-sport athlete. Four years, you leave with no degree … [Williams] leaves and raises a family and children, and he has no bitter attitude against Miami. That’s amazing. That speaks to his character. Jerry Williams was a man of character, I think.”

Myldred Boston ’49

Myldred Boston, born in Cleveland, was excited to hear from Miami University during her college admission process in the early ’40s.

“No one in my family had never [even] attended college, so [hearing from Miami] was exciting for us,” Boston said in an interview with Ellison, the professor of history and American studies and former McGuffey Museum director, on June 17, 2006.

She was also excited that Miami was one of few colleges to send her information about its academic programs.

When she got to campus for fall move-in day 1945 as one of the first two non-athletic black students to live on-campus, she saw that her room was in the basement next to the furnace room.

“I decided that wasn’t going to be where I would be living,” Boston recalled.

“I called [the Dean of Women and] asked if she would come over. We stood in the middle of that room, and I politely asked her if she would live there.”

The dean’s response was no, Boston said, “and so was mine.”

She then gave Boston a list of black families around Oxford who would house black students attending Miami.

That same year, there were only 10 black students on campus out of 5,300 students.

While Boston looked for families to stay with, her potential roommate, Arie Parks, stayed in the basement dorm and did not return to Miami the following year.

Boston lived out the rest of her first year on Vine Street, living with Mr. and Mrs. Jackson, a married couple who took her in. “[I was] still eating in the dorms [and] still having class on campus,” she said in the 2006 interview.

Boston returned to on-campus housing her sophomore year, living in the Tallawanda Apartments. Tallawanda Apartments used to sit on the northwest corner of High Street and Tallawanda Road. The site now holds Edwards parking lot, next to Old Manse.

The transition back to on-campus living was not exactly smooth for Boston.

“The young people who lived in Talawanda Hall were those young ladies whose parents were called and asked if they knew there would be a black living in that resident hall,” Boston explained. “Those who lived on the first floor were all of those whose parents consented.”

There were three floors in Talawanda, with 200 students in total.

Boston recalled living in Talawanda with her roommates to be a pleasant experience. “They were not bothered by [living with a black student],” she said. “We had met in classes and … got along well. I thought it was a real good arrangement, even though we knew it was a made-up arrangement.”

In 1946, The Miami Student published an ad on behalf of the Campus Interracial Committee. The ad requested a ratio of “two White students and one Negro student” to live in two apartments in Talawanda.

The Committee posted the ad in hopes the living arrangements would be “a contribution to better race relations on this campus.”

Even though their parents did not consent to having their daughters live on the same floor as a black student, “the women above the first floor were not bothered by it at all. So my second year really went well,” Boston said.

Boston still faced discrimination in and out of the classroom.

She took a sociology class where, on the first day, the professor told her, “without batting an eye, ‘No n****r gets more than a D in my class.’ … and I walked away with a D,” she said. “Never had a D in my life.”

And Uptown, Black students and residents had to sit in segregated seating in the movie theaters and were not allowed in most restaurants, she explained.

“The people in the town who wanted to buy sandwiches would be served from the rear of that establishment,” she said. “You’d have to go to the back of the establishment and get your brown paper bag … and I just couldn’t do that.”

The racial discrimination she experienced inspired Boston to become more involved with the Campus Interracial Committee, eventually acting as the corresponding secretary.

The Committee, made up of roughly 20 to 30 black and white students, performed sit-ins at restaurants black people were not allowed to patronize.

They also worked with the NAACP Oxford chapter as well as the congregation of Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church on Beech Street.

“We had support,” Boston said. “There were white students who were bothered by the kinds of things that they heard us talk about, and they were supportive of [us] doing the things that we did [...] the sincerity was obvious.”

Throughout her years at Miami, Boston’s persistent activism paid off.

“Those who were serving us at first didn’t serve us,” she said. “But we sat and sat, and we changed positions and others would come and sit, and all of a sudden at some point in time, we could walk in and be seated and were served.”

When Ellison asked her an important moment she would want on the record, Boston mentioned the sit-ins and desegregation of Oxford restaurants.

“That’s history,” she said. “We were able to go in and sit and be served as anyone would be.”

At the end of the 2006 interview, Boston said she felt “mixed emotions” when thinking about attending Miami during that racial climate. “For a long time, they were not pleasant,” she said, “but I would never tell anyone not to go or talk about it negatively.”

Boston’s daughter eventually attended Miami and graduated in the 1980s. According to “mublkalum” Instagram page, Boston “became engaged with Miami’s Black Alumni Advisory Committee and came back to campus on different occasions.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that Nellie Craig was the first black student at Miami University. Craig was actually the first black student to graduate from Miami. Additionally, we wrote that Myldred Boston sat in "second floor segregated seating," at Oxford's two theaters, but neither of these theaters had second floor seating. Black students had to sit in a segregated section of the theater.