Miami University is facing a budgetary problem, and unless it’s able to fix it, Miami officials worry about the longevity of the university’s reserves.

“We are going to have to tighten the belt in the next few years,” Provost Liz Mullenix said.

The problem

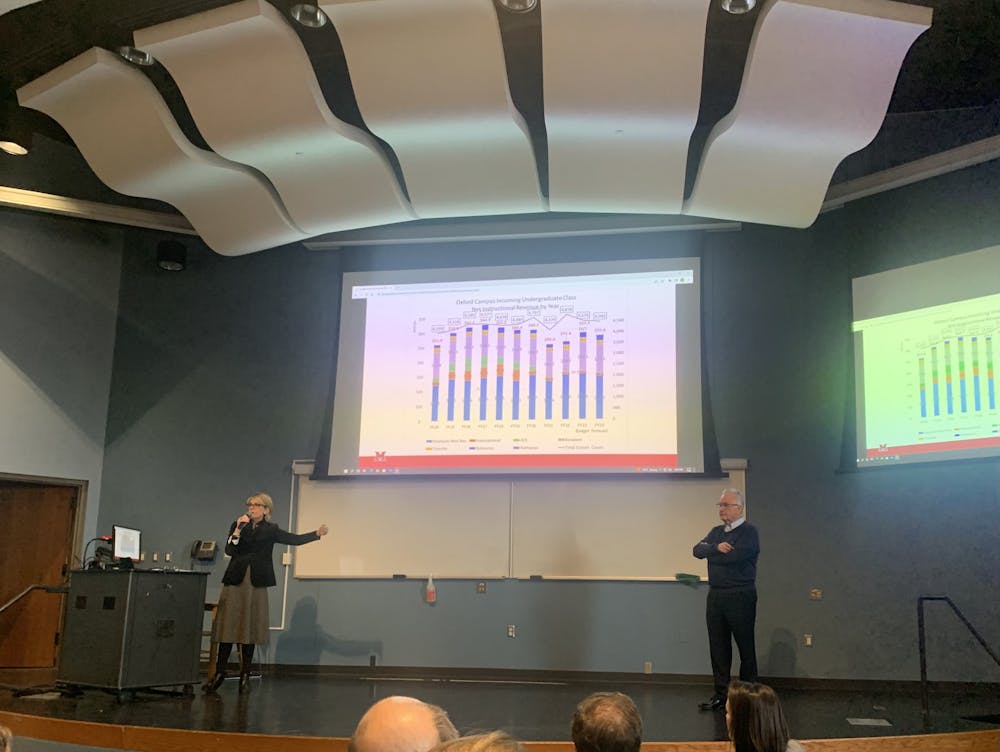

During Miami’s annual budget symposium, Mullenix said the university faces a more than $36 million budget deficit. The deficit means the provost must pull $16.2 million from university reserves. The other $20 million will be offset by open positions. Staff, faculty and other positions may be kept open to avoid drawing more from the reserves.

The symposium, which took place on Monday, Feb. 6, was led by David Creamer, senior vice president for finance and business services and university treasurer. The presentation went over Miami’s 2023 fiscal year, which began July 1, 2022, and will last through June 30.

Creamer explained the university is reacting to national trends of low enrollment for domestic and international students, as well as competition from other universities. However, the university’s decision to draw on reserves isn’t a long-term solution.

“The issue is we can’t sustain doing this in the future without finding a way to reverse the trends that we’re facing right now,” Creamer said.

The revenue gained from tuition has continued to decrease from 2018 until today — down $50 million this year from the 2018 tuition revenue. Although tuition increases each year, Miami has also been increasing the amounts given in scholarships.

“Tuition has gone up every year … It’s the discount that’s really killing us, right?” asked Todd Stuart, director of arts management and entrepreneurship.

Mullenix agreed.

“We have to discount because it’s a totally competitive market,” Mullenix said.

To ensure its incoming classes have enough diversity, high-performing students and other markers, Miami has had to discount its tuition to appeal to students. Despite the university enrolling more students than ever, Miami made less in tuition revenue in 2021 than in 2001.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

Another contributing factor to the deficit is the decreasing aid from the state of Ohio. Funds from the state are much lower than in years past, even lower than in fiscal year 2001 — the first fiscal year Creamer oversaw.

The university has continually raised tuition to account for the reduced funds from the state.

“We can go back to 1976, the year I graduated from college, tuition at Miami was $800,” Creamer said. “This fall for the incoming class, over $17,400.”

This year, Ohio’s legislation is discussing its allocation of funds to universities. Creamer isn’t hopeful the state will provide more funding.

“The strategic planning at the state has been pretty absent,” Creamer said. “This is the year that we do the budget … I expect it’s going to be a tough year.”

The university’s solution

In the short-term, Creamer said Miami will pull funds from its reserves. This upcoming fiscal year, the provost plans to pull $16 million, but in the next few years, Creamer has estimated the provost may need to pull another $25 million from the reserves.

“It’s really important that we see that return in revenue because right now we’re overspending,” Mullenix said.

Concerns were also raised about Miami hiring more professors to help with increases in healthcare and emerging technologies programs. Professors worried the increase in pay for those professors would continue to offset the budget.

Mullenix said some increases have already been taken into account. She also said she would look over which programs need to be sunset, or eliminated, to help balance the budget.

Creamer emphasized Mullenix’s role in Miami’s financial decisions.

“The provost has got the difficult job now of seeing if the goals that were set were achieved now,” Creamer said.

In an email to The Miami Student, Creamer also said some of these problems would go away as soon as the two pandemic classes (Class of 2023 and 2024) graduate and new classes enroll at Miami. Creamer wrote that during the pandemic, the two remaining pandemic-era classes were given more university scholarships to assist students and their families.

“The current budget plan assumes this will be sufficient to avoid the need for future budget cuts,” Creamer wrote. “Obviously, the budget plan will be updated each year to reflect the actual budget situation.”

The full presentation can be obtained from the Office of the Provost.