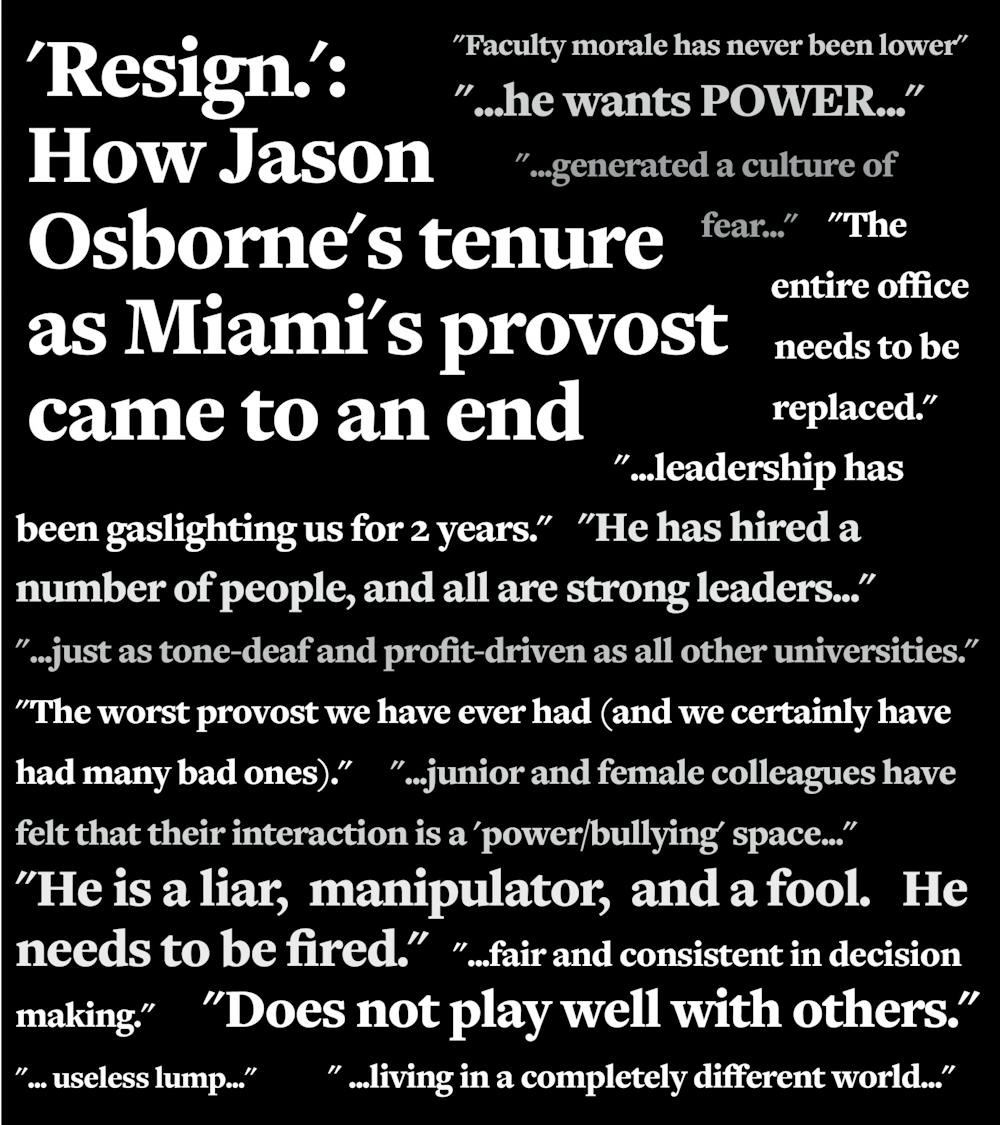

On March 17, almost a thousand faculty members were invited to take an anonymous survey to assess then-Provost Jason Osborne’s three-year tenure at Miami University.

Over the course of two weeks, more than 37% of eligible faculty members left comments on the survey. The 352 respondents left more than 1,400 comments.

Five faculty members were chosen to be part of the committee, called the All-University Faculty Committee for the Evaluation of Administrators, which reviews the results.

It was tasked with writing Osborne’s three-year evaluation report based on the survey results. After presenting its findings with the university’s president, the committee would then share the report with the rest of the Miami community.

But the report was never published.

Instead, Osborne resigned just four days before it would have been finalized.

After months of investigation, The Miami Student has obtained the survey results and a rough draft of the committee’s report through multiple public records requests. The Student has created a timeline of events leading to Osborne announcing his resignation on April 11 and the termination of the final report ahead of its April 15 deadline.

In the time since, Osborne has accepted a position as special assistant to the president, even as the university spent $24,000 on an external investigation into his conduct.

In an email to The Student, Jessica Rivinius, interim vice president for communications, wrote that Osborne would be unable to answer questions related to the story.

“Jason Osborne is unavailable to respond at this time,” Rivinius wrote. “He is on intermittent FMLA leave, caring for a terminally ill family member.”

What is a provost and why is it important?

The provost works as the chief academic officer for the university.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

According to the position description in Osborne’s personnel file, the provost has “ultimate responsibility for all academic programs, operations, and initiatives.” The provost is also expected to manage a “significant part” of the budget for academic operations.

Other responsibilities include oversight of faculty promotion and tenure and management of the administrative structures of each academic college and center at Miami. All academic deans and members of the Provost’s Office report directly to the provost.

Miami launched its Strategic Plan, a guiding document for the university’s future, in July 2019. When Osborne came to the university one month later, he had the additional responsibility for “the creation and implementation of programs consonant” with this plan. At the time of his hire, the Provost’s Office budget was $13 million.

Who is Jason Osborne?

Osborne was hired by Miami to serve as provost starting the fall of 2019. Before Miami, Osborne was dean of Graduate Studies at Clemson University and a department chair at the University of Louisville.

According to his resume when he applied to Miami, Osborne has worked at seven different colleges and universities since 1993, now eight including Miami. Ohio is the seventh state where he’s held a job in higher education.

During his tenure at Miami, Osborne helped oversee the implementation of a new strategic plan, the creation of the Honors College and the transformation of the Global Miami Plan to the Miami Global Plan.

Within Osborne’s first year as provost, Miami also shut down in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, leaving him to lead the university in unprecedented times.

In an email to The Student, President Greg Crawford praised Osborne for his work as provost.

“During his tenure as provost and executive vice president for Academic Affairs, Dr. Osborne helped to lead the university through an unprecedented and uncertain time in higher education due to the COVID-19 pandemic,” Crawford wrote.

Rivinius echoed Crawford’s praise in another email to The Student.

“Jason's leadership throughout the period of Covid-19 was greatly appreciated and his work on the Miami University strategic plan and Boldly Creative helped to establish the positive trajectory for Miami's future,” Rivinius wrote.

What’s a third-year evaluation?

The faculty committee which evaluates administrators reviews the provost, all academic deans, the associate provost for research and dean of the graduate school, the dean and university librarian and the university director of Liberal Education in their third and fifth years at Miami.

Members are chosen by their academic divisions through University Senate election procedures. Osborne’s committee was originally made up of seven faculty members, Terri Barr, Stephanie Baer, Ginny Boehme, Daniel Hall, Andrew Paluch, Phillip Smith and Cathy Wagner. However, after Smith and Wagner recused themselves from working on the report due to conflicts of interest, Osborne’s committee ended up with five members.

The review is intended to help with the professional development of these administrators and help base future decisions for these positions. All responses made on the survey are anonymous.

Third-year reviews for administrators ask a set of standard questions, and the administrators being evaluated are also allowed to add questions of their own.

Paluch, an associate professor in chemical engineering, was chosen by the committee to be the chair during its review of Osborne. Paluch said the wording of some questions had to be updated over time, and Osborne gave feedback for the standard questions as well as his own additions.

Paluch said Osborne seemed excited about the prospect early on in the process.

“He was all in,” Paluch said. “... He was excited that he was going to get some feedback that he could use in some constructive way to make himself better. He was maybe a little too into it in terms of going back and forth with questions.”

When the raw survey results came in, the comments painted a less than rosy picture.

The survey by the numbers

Based on the responses, Osborne was not a popular provost.

The survey included 37 questions ranked on a scale from one to five, following the Likert scale. A score of one meant the survey respondent strongly disagreed, while a five meant the respondent strongly agreed.

Across the quantitative questions, Osborne’s highest average was 2.83 in supporting appropriate technology resources — less than a neutral response of 3.

He earned his lowest score, 1.51, in valuing and achieving high faculty morale.

Osborne’s review also motivated significantly more faculty members to respond to the survey compared to the previous provost, Phyllis Callahan. In 2016, Callahan received about half as many responses as Osborne did with a response rate of only 21%. Callahan received an average score between 3 and 4 on all but one section where she scored a 2.96 for valuing and achieving high faculty morale. Callahan retired after serving four years as the provost.

The Student is publishing the survey results online. The Student has decided to exclude a portion of one comment to balance the public’s need for information against harm in accordance with the Society of Professional Journalists Code of Ethics. The document also includes sections marked “Redacted” where Miami’s General Counsel has removed sections that it believes is not something that should be available to the public.

Because Miami is a public university, it has to submit to public records requests, such as the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. Over the course of its investigation, The Student submitted multiple FOIAs to obtain relevant documents.

The editorial staff collaborated with a lawyer and an expert on media ethics before deciding to include the results in its final report. As a public record, anyone has the right to request the survey results under Ohio Open Public Records and Open Meetings laws, or Sunshine Laws.

The survey by the comments

In addition to the quantitative questions, participants were invited to answer short response questions. Even though fewer than 400 of the 939 people filled out the survey, they left a combined total of more than 1,400 comments.

“The sheer volume was overwhelming, to say the least,” Paluch said.

While the majority of comments were negative, going so far as calling Osborne a “useless lump” and other derogatory names, some positive comments shone through. One anonymous respondent referred to Osborne's leadership as “one of courage, diligence, vision.”

“The amount of people that take the time to actually fill out the short answer questions is usually pretty small,” Paluch said. “[With] the provost, it seemed like everybody took the time to fill them out.”

Beyond a question specifically asking for positive aspects of Osborne’s tenure, in which more than a third of respondents wrote that they had nothing good to say, few comments were supportive. Many positive comments related to his decision-making and communication around health and safety during the pandemic.

Many comments criticized problems with shared governance, diversity and inclusion and hiring decisions.

Hesitancy to share

A committee member, who wished to remain anonymous, shared that the responses in the survey might not have even reflected the whole story.

“For some of the more serious comments and allegations, there wasn’t a whole lot of detail, and I think it’s because, for one thing, the people who were mentioning it might have been scared of retaliation,” the committee member said. “The comments were supposed to be anonymous, but they were also administered through Miami’s Qualtrics, and so there was probably a little bit of hesitancy from some people about that.”

Some respondents mentioned this in their answers.

“It is unbelievable that this survey would include this question,” one respondent wrote, answering a question about strategic initiatives that should receive attention in the future. “Any specific recommendations will clearly identify respondents.”

Shared governance

In an email to The Student, Rivinius and Director of Executive Communications Ashlea Jones explained that shared governance refers to faculty and administrators working together “toward providing a rigorous academic experience” for students.

“We value – and have always valued – our system of shared governance and continually seek ways to bring more voices to the table,” the email read. “Core to our system of shared governance is University Senate, the primary university governing body comprised of students, faculty, staff, and administrators.”

Despite this, many faculty members used Osborne’s third-year review to express their dissatisfaction with how the model has functioned in the past three years.

“[Osborne] has been the opposite of shared governance,” one faculty member wrote. “He makes decisions and presents them rather than inviting discussion and majority decision making. People don't feel respected by him or his leadership. They feel diminished and discounted. He has no trust in the expertise within the institution.”

One question asked respondents to answer if they agreed or disagreed that Osborne “respects the role of faculty and staff in shared governance.” More than 80% of respondents either disagreed or strongly disagreed.

One commenter wrote that Osborne welcomed faculty input for “minor” issues such as the university’s contract with Proctorio, a test-proctoring service. On “major” issues like the termination of Visiting Assistant Professors (VAPs), though, the commenter said he acts “without regard for faculty input.”

Another response suggested that the university’s respect for shared governance is at its lowest in 30 years or more.

While the University Senate has multiple committees for specific issues at the university, including the committee which conducted the third-year review, some felt the current avenues aren’t enough.

“Just serving on committees, does not equate shared governance,” one faculty member wrote.

Along with a perceived decline in faculty power, several commenters also mentioned a rise in administrative positions. According to a 2017 article in Forbes, the ratio of faculty to administrators has declined in higher education across the board, indicating an increase in the number of administrative positions, while administrative spending has increased since the 1980s.

“The Provost's office has also been the site of the sort of administrative bloat that has plagued higher education in the US for some time now,” one commenter wrote. “In addition, this bloat has come by empowering non-faculty administrators as supervisors of faculty. If the goal is really shared governance, then there needs to be less centralization of power in the Provost's office and less delegation of power to non-faculty administrators.”

Osborne and FAM

Miami faculty members announced their intentions to unionize as the Faculty Alliance of Miami (FAM) on Feb. 2. Based on several survey responses, Osborne’s tenure as provost was a major motivating factor for many to join the cause.

“I am iffy on the question of the union,” one respondent wrote, “but what I have witnessed by this provost has pushed me to join FAM.”

Even those against the union recognized Osborne’s central role in its formation.

“Your current management style, disregard of shared governance, centralization of power/finance, non-transparency, extremely poor decision making, disregard of opinions coming from departments/divisions etc., are the primary reasons the union was set into motion,” one faculty member wrote. “Therefore, in order to preserve the current structure and potentially prevent a union from forming, for the well being of the university I urge you to step down from the role of provost.”

Two days after Osborne’s resignation, the FAM announced it was moving from looking for signatures in support of the union to authorization cards that would allow it to file for a vote.

The VAPs, revisited

VAPs are faculty members that the university hires on one-year contracts for up to five years to assist departments with teaching workloads. In 2019, the university had 252 VAPs.

That number soon dropped.

In 2020, as the university shut down due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Osborne chose not to renew the contracts of more than half of VAPs, dropping the number of VAPs to 107.

In an email to The Student, Rivinius explained that a dip in enrollment also meant a decrease in the need for more VAPs.

“In 2020, there was a dip in enrollment, caused by students deferring or pausing their college journey because of the pandemic, leading to a decreased demand for positions categorized as Visiting Assistant Professors,” Rivinius wrote. “All departments received the visiting faculty they requested.”

In the survey, 74 responses directly mentioned this loss of VAPs, with many responses criticizing the decision.

“[H]is utter lack of support for DEI [diversity, equity and inclusion] is shown in the sacking of the VAPs, a cohort in which the underrepresented are more numerous,” a respondent wrote. “That he then tried to turn this into a horn blowing celebration, noting that he had increased the percent of tenure track faculty was beyond appalling. Only the most bilious of toads could have made that despicable claim.”

Other respondents said the decision came as a surprise to them.

“The nonrenewal of potentially over 100 VAPs in 2020 — with no meaningful financial rationale shared with us — was an irresponsible decision, the impact of which we are still struggling to understand,” one respondent wrote.

However, at the time, Osborne said the cuts were made for financial reasons, and he asked for departments to reduce the number of courses being offered which led to a decrease in need for VAPs.

In 2021, Miami’s Board of Trustees, due to a larger-than-anticipated amount of funding and the largest first-year class in Miami history, approved for $24.6 million to be spent on VAPs.

Criticisms of diversity and inclusion

When Osborne first arrived at Miami, he hoped to improve diversity and inclusion on campus, even partially taking on fulfilling the Climate Survey Task Force recommendations, which had a focus on improving the university’s diversity and inclusion.

In an email to The Student, Rivinius said Osborne also helped with another task force regarding diversity and inclusion.

“In 2020, Miami University President Gregory Crawford appointed the President’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) Task Force to make recommendations aimed at building a more inclusive, diverse, safe, and welcoming climate,” Rivinius wrote. “Jason Osborne has been a part of these efforts. Inclusive excellence is part of every single one of the university’s goals.”

Rivinius said since the task force was started, it has achieved 91.9% of the 44 recommendations it presented in 2020.

Some comments applauded Osborne’s work with diversity and inclusion, especially with the Heanon Wilkins Faculty Fellow Program, which recruits 10 culturally diverse scholars to train for a career in higher education each year.

“The DEI and global affairs components of his position are some of the strongest parts of Provost Osborne’s portfolio,” a respondent wrote. “He has added diversity to his senior staff, supported and stabilized our international presence, and he has worked with departments to firm up the Wilkins fellows.”

However, other survey comments did not agree that Osborne was helpful to improving the university’s diversity and inclusion.

“The Provost allows some people to speak and values their opinion more than others,” one respondent wrote. “Even though he is a strong advocate for DEI, his personal approach to who he listens to and allows to speak says otherwise.”

Some comments called out the entire university for a lack of focus on diversity and inclusion during Osborne’s tenure.

“As a female person of color, I have felt even more excluded than at any point in my university career,” one respondent wrote. “At least in the past there was token representation.”

Problems in the Provost’s Office

Some respondents pointed out aggressive behavior they witnessed from Osborne.

“[H]e is a bully,” one respondent wrote. “I have personally watched him bully (or try to bully) women, people of color, and men whom he sees as weak.”

The rest of the comment was redacted.

The same anonymous member of the committee said some of the comments mentioned such concerning topics that General Counsel was consulted. Rivinius confirmed that Paluch went to General Counsel, who then coordinated with the Office of Equity and Equal Opportunity (OEEO) to investigate the claims made against Osborne.

“One of the allegations was serious enough that the chair of our committee scheduled an emergency meeting with the General Counsel to basically ask, ‘What the fuck do we do?’ pardon my French,” the committee member said.

On May 2, a Miami employee also filed a complaint against Osborne with OEEO, a department promoting fairness and justice that ultimately reports to the president's office. The complainant argued that she was paid unequally based on sex, sexual orientation and disability.

Miami had already hired an outside law firm, Keating Muething & Klekamp (KMK), to investigate the similar claims made in Osborne’s survey results. The investigation cost the university $24,000.

“Some of the responses also included potential reports of harassment, discrimination, hostile work environment based on various protected classes, including sex, sexual orientation, race, and generalized concerns of retaliation,” KMK’s investigation report read. “OEEO also noted that it had received several complaints from other Miami employees regarding alleged discrimination by [Osborne] on the basis of sex, sexual orientation, as well as claims of retaliation.”

However, after interviewing people deemed to have potentially relevant information, KMK wrote in its report that it “was unable to substantiate these allegations.”

Rivinius wrote in an email to The Student that only one formal complaint was made against Osborne. The other complaints were informal, meaning OEEO could not further investigate them.

“The only formal complaint made against Jason Osborne, which was made May 2, 2022 (a few weeks after [he] announced his decision to step down as provost), was thoroughly investigated and deemed unsubstantiated by KMK,” Rivinius wrote.

What happened after the survey came back?

On Friday, April 1, Ted Pickerill, executive assistant to the president, was sent the raw survey results and shared it with Paluch. In emails obtained by The Student through a FOIA request, Pickerill wrote of his intent to share the data with both Crawford and Osborne himself.

In the emails, Paluch pushed back.

“My opinion would be to go ahead and share with the President,” Paluch wrote. “Then our report is due to the President on April 15, after which a summary report is prepared. Would it be better to share the raw data with the Provost at the same time our report is shared with him? … My thought process is if the data would be easier to digest when shared with our summary.”

Pickerill responded with the university’s policy text on the committee’s procedures. In it, he highlighted a section that reads, “The supervisor [Crawford] and the administrator being evaluated [Osborne] shall have access to all of the faculty responses, including survey results and transcribed copies of comments.”

The policy does not specify when the survey results should be shared with either the supervisor or the administrator being reviewed.

In a further email, Pickerill clarified that he made the decision to share the data with both Crawford and Osborne to make the process more open.

“With the policy specifying the supervisor and the evaluee have access, for transparency sake, providing everyone with access at the same time seemed most appropriate,” Pickerill wrote.

Osborne would announce his resignation 10 days later.

Osborne’s resignation

On Friday, April 8, Crawford signed a letter approving Osborne’s resignation. That morning, Pickerill emailed Paluch, saying that the committee could have until April 18 to finish the report if they couldn’t make the April 15 deadline.

Osborne announced his resignation in an email to all faculty at 5:31 p.m. April 11.

Multiple comments in the survey results had directly called on Osborne to resign. One respondent put it succinctly in a question asking for specific suggestions: “Stop rewarding bad behavior. Give people regular leave. Resign.”

Rivinius shared in an email to The Student that Osborne’s resignation was based on personal matters.

“As Jason Osborne shared in an email to the Miami community on April 11, 2022, his decision to step down as provost was a personal decision, made with his family,” Rivinius wrote. “He later shared that this decision was influenced by his desire and need to focus on his family as they have been battling serious health issues.”

Eight minutes after Osborne’s resignation email, Pickerill emailed Paluch and told him that a final report was “no longer required.”

At 5:44 p.m., committee member Daniel Hall emailed the committee about the importance of maintaining a record and suggested they finalize the report regardless.

At 6:15 p.m., committee member Ginny Boehme offered her support. Neither had seen the email from Pickerill at this point, which had been sent to Paluch only.

At 11:40 p.m., Paluch shared Pickerill’s email with the committee and said he supported finalizing the report to offer an explanation for why Osborne resigned and help provide insights for future administrators.

“There is also the issue of accountability,” Paluch wrote. “Since the Provost is now resigning, is everything erased from history?”

Paluch did not respond directly to Pickerill until the next morning. He asked Pickerill for advice on how to proceed. Pickerill replied just a few minutes later asking Paluch to acknowledge his first message, which asked the committee to stop the final report.

That afternoon, Pickerill sent a detailed follow-up citing language from the university policy library that said a report would only be published “[i]f the administrator is continuing in his or her position for at least one (1) more year.” He also cited a court case from Blue Ash, where assessments of managers in the city were not deemed “subject to release under Ohio public records law” as they were only being used for development purposes.

When The Student requested the raw survey results through a FOIA, the university complied, indicating that the results were public record.

On April 13, Paluch emailed then-executive assistant to the provost, Stacy Kawamura, that the report would not be finished.

“The President's Office has killed the Provost's evaluation,” Paluch wrote. “They do not want a report and do not want anything released.”

Osborne’s new job

On April 8, three days before announcing his resignation, Osborne received a letter from Crawford accepting his resignation.

In the letter, Crawford also offered Osborne the role of Special Assistant to the President for July 1, 2022, to Dec. 31, 2022. Osborne would keep his salary until that date, which at the time was $390,000 a year.

“In this role as Special Assistant to the President, you will undertake all such duties as may be assigned by the President of Miami University to the benefit of the university,” the letter read. “You shall devote your full time, attention, skill, and efforts to the faithful performance of your duties, and will continue to receive the benefits customary with an administrative appointment of this type.”

In an email to The Student, Crawford said Osborne would be working on some of the programs he started as provost.

“Dr. Osborne is serving as a special assistant in the President's Office this fall until he transitions back to faculty in the spring,” Crawford wrote. “In this role he is completing the many important initiatives he has worked on as Provost, supporting the leadership transition in Academic Affairs, and supporting University Advancement’s work on the capital campaign.”

After he finishes the role, Osborne will receive a tenured faculty position in the Department of Statistics with a nine-month salary of $195,000.

According to the Buckeye Institute, which compiles salary data for public universities in Ohio, the highest-paid faculty member in statistics, the chair of the department, in 2019 made $225,247 for 12 months. The next highest salary was $103,205 over nine months, just more than half of what Osborne will make as a faculty member next year. The average nine-month pay for faculty members in statistics at Miami in 2019 was $74,899, and the median pay was $79,788 — both less than half what Osborne will earn.

The letter also said he would be given a paid leave for the spring semester of 2023, keeping his salary and benefits, while preparing to return to faculty. He would teach one class his first semester, then two classes his second semester, before receiving a teaching load following university policies, which generally require professors to teach at least 6 credit hours each semester — terms he had been offered when he accepted the role as provost. He would also receive a one-time payment of $75,000 for “startup funding” for faculty transition in Spring 2023.

Osborne signed the letter, agreeing to these terms, the same day Crawford offered him the position.

Osborne’s response will be recorded at miamistudent.net when he returns from intermittent family and medical leave.

Additional reporting by Abby Bammerlin, Cosette Gunter-Stratton and Alice Momany.

For an overview of our reporting and publishing process, refer to Staff Report: "How we conducted our investigation on Jason Osborne's resignation."