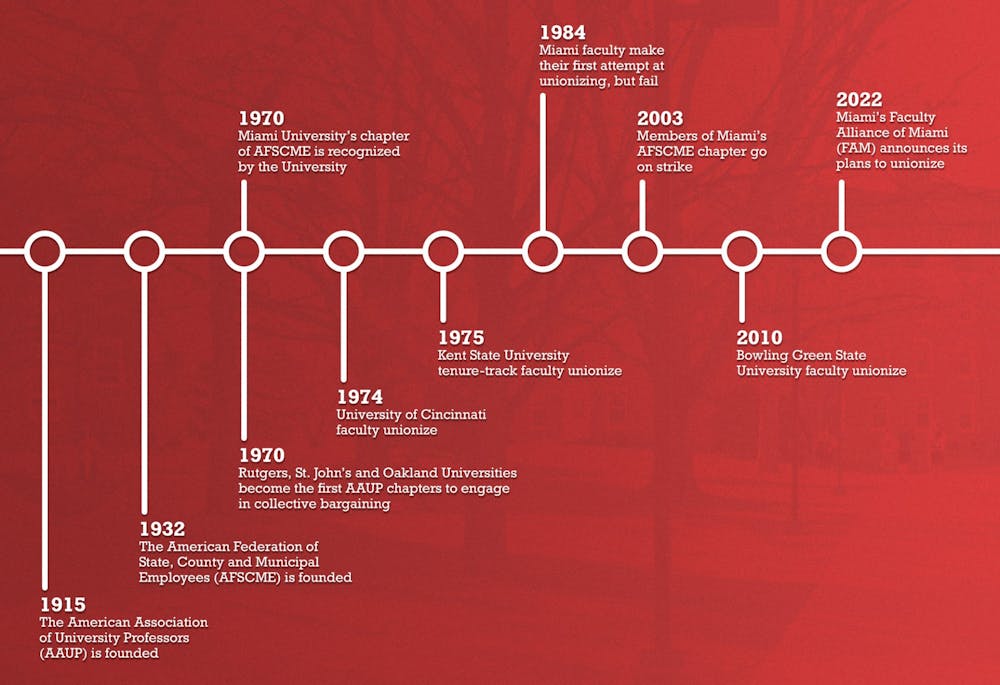

If Miami University faculty vote to form a union, Miami will become the tenth of 14 public four-year universities in Ohio to host a faculty union. As that number shows, faculty unionization is far from unprecedented in Ohio and elsewhere.

However, unionization isn’t unprecedented at Miami either.

Though the Faculty Alliance of Miami (FAM) would be Miami’s first faculty union, the university has a history of labor activism that spans more than 50 years.

Local 209

When rumors of an employee union began swirling around Miami’s campus in early 1967, Director of Personnel Ed Jackson did all he could to convince staff members organizing wasn’t necessary.

In an Oct. 28, 1967 letter to all non-academic employees, Jackson reminded the recipients of Miami’s recent staff welfare initiatives, including a 5% pay raise earlier that year and free life insurance.

Miami employees had it pretty good, Jackson argued – in fact, unionizing would only make things worse.

“It is significant to know that at two State universities in Ohio where unpleasant labor situations developed,” Jackson wrote, “there still has at this time been no actual salary improvements for all their employees.”

The two universities Jackson refers to are Ohio University and Ohio State University, both of which were temporarily shut down by strikes from their local chapters of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME).

Miami’s chapter of the AFSCME, Local 209, was founded in 1967 but didn’t successfully secure a bargaining session with the university until 1968. Miami’s administration only agreed to negotiate with the union after repeated strike threats from Bill McCue, international coordinator of the AFSCME.

“If I can get Jackson to the bargaining table,” McCue said to a reporter for The Miami Student in 1967, “[U.S. President Lyndon] Johnson ought to hire me to get Ho Chi Minh there.”

Perhaps McCue was on to something – Johnson would leave office before the U.S. left Vietnam, but McCue succeeded in getting Jackson to enter negotiations just a few months later.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

In 1970, the university officially recognized Local 209, and the two parties signed their first collective bargaining agreement (CBA), which they continue to revisit every three years.

Any full-time, non-academic, non-supervisory Miami employee has the option of joining Local 209, but all employees benefit from the terms of the CBA. Employee guarantees that have existed since the first CBA include free tuition for employees, two paid 15-minute breaks per eight-hour shift, and partially-covered health insurance.

One term of the early CBAs, though, was that the union was not allowed to strike.

Faculty Association

Miami’s administration may have preferred to avoid any unions on campus, but it learned to live with Local 209. As long as the one class of employees not eligible to join the union – the faculty – weren’t attempting to organize, all was well.

It was only a matter of time, though – chapters of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) began formally unionizing in the 1970s, including University of Cincinnati in 1974 and Kent State University in 1975.

The Miami University Faculty Association (MUFA) lagged behind these peer institutions by about a decade, but in 1984, a new Ohio law set MUFA’s unionization efforts into motion.

Section 4117.03 of the Ohio Revised Code gives public employees – including faculty at public universities – the right to form “employee organizations” for the purpose of collective bargaining with their employers.

Though faculty unions had existed since the late 1960s, this new law gave them new leverage.

In a March 6, 1984 letter to all faculty and unclassified staff, Miami President Paul Pearson wrote candidly about his fears regarding a faculty union, but also opened himself up to the possibility of negotiation.

“I am convinced that unionization would not be in the best interest of the faculty, staff or of Miami University,” Pearson wrote, “[But] certainly, if the faculty and staff have an interest in collective bargaining, there should be open and full discussion where each person would have the opportunity to express himself or herself.”

A letter sent to faculty by MUFA President Peter Rose made it abundantly clear that the group was interested in collective bargaining.

The letter states that collective bargaining was “the most promising option for faculty” in the face of a number of issues, including diminishing salaries, reduced faculty participation in decision-making and a failure to evolve the university’s purpose “in a period of radical change.”

Rose also wrote that Kent State’s faculty union dramatically increased salaries through collective bargaining.

MUFA spent five years soliciting support from faculty members, and in April 1989, a vote was held to determine whether the faculty would unionize.

87% of eligible faculty voted; 63% voted against the union.

Five years of coordinating became moot in an instant, and Miami’s first attempt at unionization faculty was defeated.

AFSCME Strike

2003 was a major year for the Miami RedHawks football team: they finished the season ranked 10th in the nation and won the MAC Championship for the first time since 1986.

The team’s first home game of the season was the traditional “Victory Bell” game against the University of Cincinnati, held on Sept. 27. The game was set to broadcast on ESPN, but the broadcast was canceled.

Local 209, Miami’s employee union, was striking, and protestors had made their way to Yager Stadium.

The strike, which lasted from Sept. 25 to Oct. 8, was more than a decade in the making. Employee wages had stagnated since the early 1990s, and negotiations for raises had been unsuccessful.

The union and Miami’s administration brought in a third-party group from the State of Ohio Employment Relations Board to objectively evaluate employee salaries. The group found the employees were entitled to a 25% increase in wages over the next three years.

The administration rejected this proposal and countered with an offer of an immediate 4.25% raise, with an extra 3% per year over the next two years. This proposal would result in a total raise of 10.25%.

The union rejected the counterproposal. With neither side budging, a strike became inevitable.

More than 900 dining employees, janitorial workers and groundskeepers participated in the strike, forcing the university to hire temporary replacement staff. Still, less than half of eligible employees were union members, and about 60% of employees reported to work during the strike.

Though the majority of staff was not striking, the labor stoppage was a visible, highly publicized event. On the first day of the strike, workers erected a 15-foot inflatable skunk outside Shriver Center (because they believed Miami’s salary proposal stunk).

Students and professors stood in solidarity with the striking staff, with students refusing to eat at the dining halls and professors holding classes off campus. Students led several major protests, including the aforementioned at Yager Stadium, one at Hamilton Dining Hall and one at the newly-dedicated MacMillan Hall.

Despite support from select students and faculty, the union grew tired as the days passed, and their optimism about receiving a better salary deal began waning. Most students also did not boycott the dining halls, so the university experienced no loss of profit during the strike.

On the 13th day of the strike, the workers voted to accept the university’s salary proposal, and the work stoppage ended.

The first strike in Miami’s history had failed.

Local 209’s current CBA will expire on June 30, so negotiations for a new one will be underway soon.

Before long, though, FAM may be engaging in negotiations of its own.

Additional reporting by Asst. Campus & Community Editor Sean Scott