A version of this column was published by the Oxford Free Press on Feb. 15, 2025.

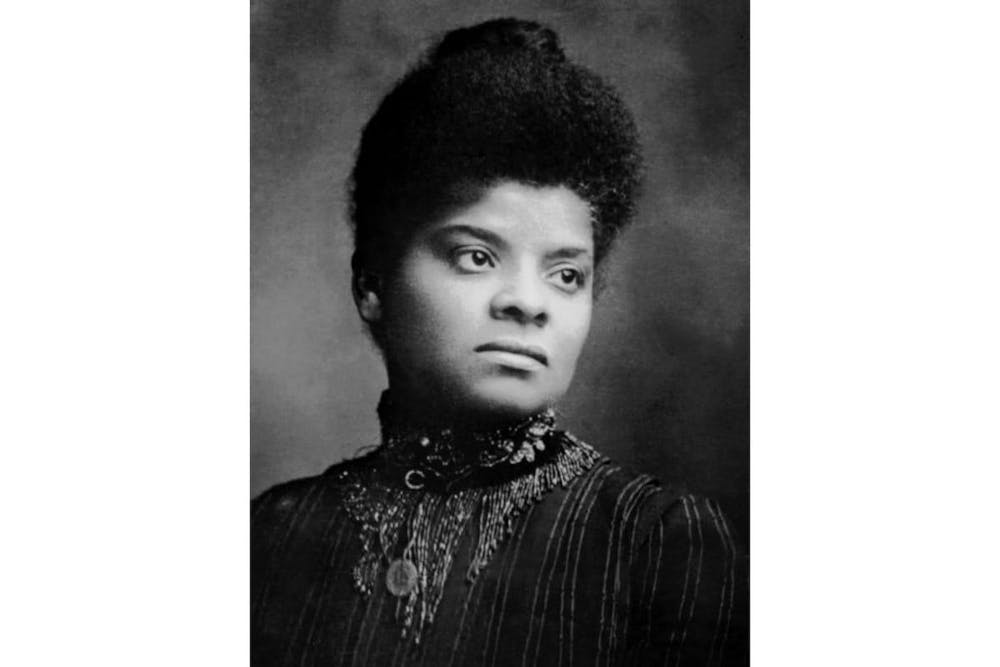

Long before there was Rosa Parks, there was Ida B. Wells.

In 1883, Wells boarded a train on her way to her teaching job near Memphis, Tennessee. The Civil Rights Act of 1875 had been overturned by the Supreme Court, and post-Civil War Reconstruction had ended several years earlier. Wells had a first-class ticket for the “ladies car,” but the conductor asked her to move to the “smoking car,” where Black passengers sat.

Wells refused.

In her autobiography, Wells recounted how a conductor and two other men forced her out of her seat and off the train. She sued the railroad company and won a $500 settlement, but the Tennessee Supreme Court overturned the verdict and charged Wells $200, claiming she was aiming to harass the company and that “her persistence was not in good faith.”

Wells was undeterred. She would go on to become an activist, writer, editor and a co-founder of the NAACP. A pioneer in investigative journalism, she developed data collection and interview techniques, waging a nationwide anti-lynching campaign. Historians say she was the most famous Black woman in the United States during her lifetime.

Wells was born in 1862 in Holly Springs, Mississippi, the oldest of seven children, to parents who were enslaved until the Emancipation Proclamation. In 1878, while visiting her grandmother, Wells’ parents and younger brother died of yellow fever. She dropped out of high school to help take care of her family and earned a teaching certificate on weekends.

In Memphis, Wells began her journalism career freelancing for various Black publications. In 1885, at age 23, she became editor of The Evening Star. Her articles about Black life and racism became popular, appearing in many of the 200 Black newspapers in the U.S. at the time. In 1889, she joined the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight as a reporter and co-owner.

A key moment in Wells’ life came in 1892, after a close friend, Thomas Moss, and two other Black men were murdered by a lynch mob after a fight among Black and white kids shooting marbles escalated. Wells covered the murder, decrying the lynching, exposing gaps in the official story and highlighting racism as the cause. Five months later, while she was out of town, a white mob set fire to the newspaper building, destroying the presses. Wells did not return to Memphis.

With New York as her new home base, Wells took a reporting job at the New York Age newspaper. She began travelling through the South to document other lynchings, accumulating data on over 700 cases. Only a third of those she covered involved criminal allegations, dispelling the widely accepted myth in the white press that vigilante mobs were somehow justified in killing Black men and boys. In October 1892, she published her famous pamphlet “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.”

The next year, Wells moved to Chicago and protested the exclusion of Black Americans at the World’s Fair. In front of the Haitian exhibit hall, Wells handed out 10,000 copies of “The Reason Why The Colored American is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition.” The pamphlet was co-written by Frederick Douglass and Ferdinand Barnett, a civil rights activist, lawyer and newspaper editor who Wells married in 1895. Douglass was the only Black invitee to the World’s fair — and he had been invited, not by the U.S., but by Haiti.

After the fair, she continued her reporting. In 1984, she gave a series of lectures in Great Britain in 1894, drawing international attention to lynching and racism in the U.S.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

After her marriage, Wells changed her last name to Wells-Barnett and had four children. She became editor of the Conservator, founded by Barnett as Chicago’s first Black paper, and Barnett often watched the kids when Wells was away on the lecture circuit.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett died in 1932 at age 68. Eight decades later, the New York Times included her in its “Overlooked” obit series on historical figures whose deaths had gone unreported by the Times. In 2020, she received a posthumous Pulitzer Prize.

Two years later, the Emmitt Till Antilynching Act passed, identifying lynching as a federal hate crime offense. The bill was named after a 14-year-old who was brutally murdered by two white men, both acquitted by an all-white jury. They later admitted to the murder and sold their story to a magazine. Till’s mother, Mamie Till Mobley, insisted on an open casket funeral in Chicago, and the photos became an early catalyst for the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Wells-Barnett wrote about the threats she faced throughout her life: “I felt that one had better die fighting against injustice than to die like a dog or rat in a trap. I had already determined to sell my life as dearly as possible if attacked. I felt if I could take one lyncher with me, this would even up the score a little bit.”

Richard Campbell is a professor emeritus and founding chair of the Department of Media, Journalism & Film at Miami University. He is a co-founder of the Oxford Free Press.