Russia is placing troops at the Ukraine border. The Olympics are being used as a political standoff. NATO member nations are trying desperately to present a united front and warn Russian President Vladimir Putin to stand down.

Is it the Cold War again?

No.

Tensions may be high, but the relationship between the United States and Russia is nowhere near the lows the country saw when dealing with the Soviet Union in the decades after World War II. As BBC reported in 2012, both countries have steadily limited their nuclear stockpiles, and mutually assured destruction isn’t at the forefront of people’s minds as it was during the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s.

But even Oxford wasn’t free from fears of nuclear warfare at the height of the Cold War. In fact, the conflict’s memory lives on in a scattered collection of structures off Taylor Road and Todd Road, where the U.S. military planted a missile base to defend Cincinnati from Soviet attacks.

Cincinnati’s first line of defense

Before the Intercontinental Ballistic Missile was a twinkle in the military’s eye, major population centers relied on a different type of protection: Nike anti-aircraft missiles.

Named after the Greek goddess of victory, Bell Laboratories began developing the defensive missiles in 1945, four years before the Soviet Union tested its first nuclear weapons. The first Nike missiles reached 68,000 feet into the atmosphere, though later models could be equipped with nuclear warheads and flew higher and faster at 3,000 miles per hour.

To reach its 1967 peak of more than 31,000 warheads, the U.S. needed uranium. Lots of it.

Enter Fernald, Ohio.

Located 20 miles south of Oxford with a population of 30, Fernald checked all the boxes the Atomic Energy Commission was looking for a new uranium processing center.

“There are no cemeteries to relocate; no schools to be affected,” one U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) spokesperson said in March 1951 when the site was selected. “It is not likely that any roads or highways will be disturbed.”

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

Though the Feed Materials Production Center, more commonly known simply as Fernald, wouldn’t be finished until Oct. 1954, it began operations three years earlier in Oct. 1951. The site covered 1,050 acres and employed 2,800 people.

It also put a target on Butler County’s back.

Not only was southwestern Ohio a major population center, with Cincinnati situated less than 40 miles from Oxford, but it was now essential to defense operations.

Fast forward to 1958. The USACE alots $3 million to build four Nike missile bases surrounding Cincinnati in Wilmington and Felicity, Ohio; Dillsboro, Indiana and Oxford. Each base would be equipped with Nike Hercules missiles, 41-foot surface-to-air behemoths with 75-mile ranges.

The next step for the engineers was to pick specific sites.

A community divided

In Feb. 1958, the Journal-News reported that government surveyors were seen near Todd and Taylor Roads off Route 27 for the Oxford base. Plans were moving quickly, it seemed.

In May, the Oxford Press raised questions about putting missile silos in Oxford. Earlier that month, eight Ajax missiles exploded at a similar base in New Jersey, killing 10.

The Hercules missiles which would be stored in Oxford were designed to be significantly more powerful.

The Ohio Farmers Union urged residents to protest, and Congressman Paul Schenk sent a telegram to the Army asking for a full investigation into the decision to locate the base in Oxford.

Even Miami University President John Millett spoke against the proposed base saying the military should look for a more remote location.

County Commissioner Ben Van Gorden didn’t mince words.

“We certainly don’t want the county sitting on a powder keg.”

Christine Shera and her husband Lloyd owned the surrounding farmland. In an interview with the Journal-News in 2001, she said they weren’t given a choice in ceding their land.

“They had it all picked out,” she said. “It was right out of the middle of the farm. It wasn’t very nice.”

Kindness aside, the USACE had started accepting bids for construction of the base before final land negotiations had been completed.

In June, Colonel Andrew Samuels of the U.S. Army Air Defense Command attempted to quell the community’s fears at an Oxford Kiwanis Club meeting.

“With the development of the atomic bomb, it is vital that not a single plane get through our defenses,” Samuels said, adding that a single Hercules missile could take out entire enemy formations.

Eventually negotiations for the land wrapped up, and construction got underway later that summer. It wouldn’t be opened until Feb. 1960, though, giving the community nearly two years to warm to the idea of a military base in its backyard.

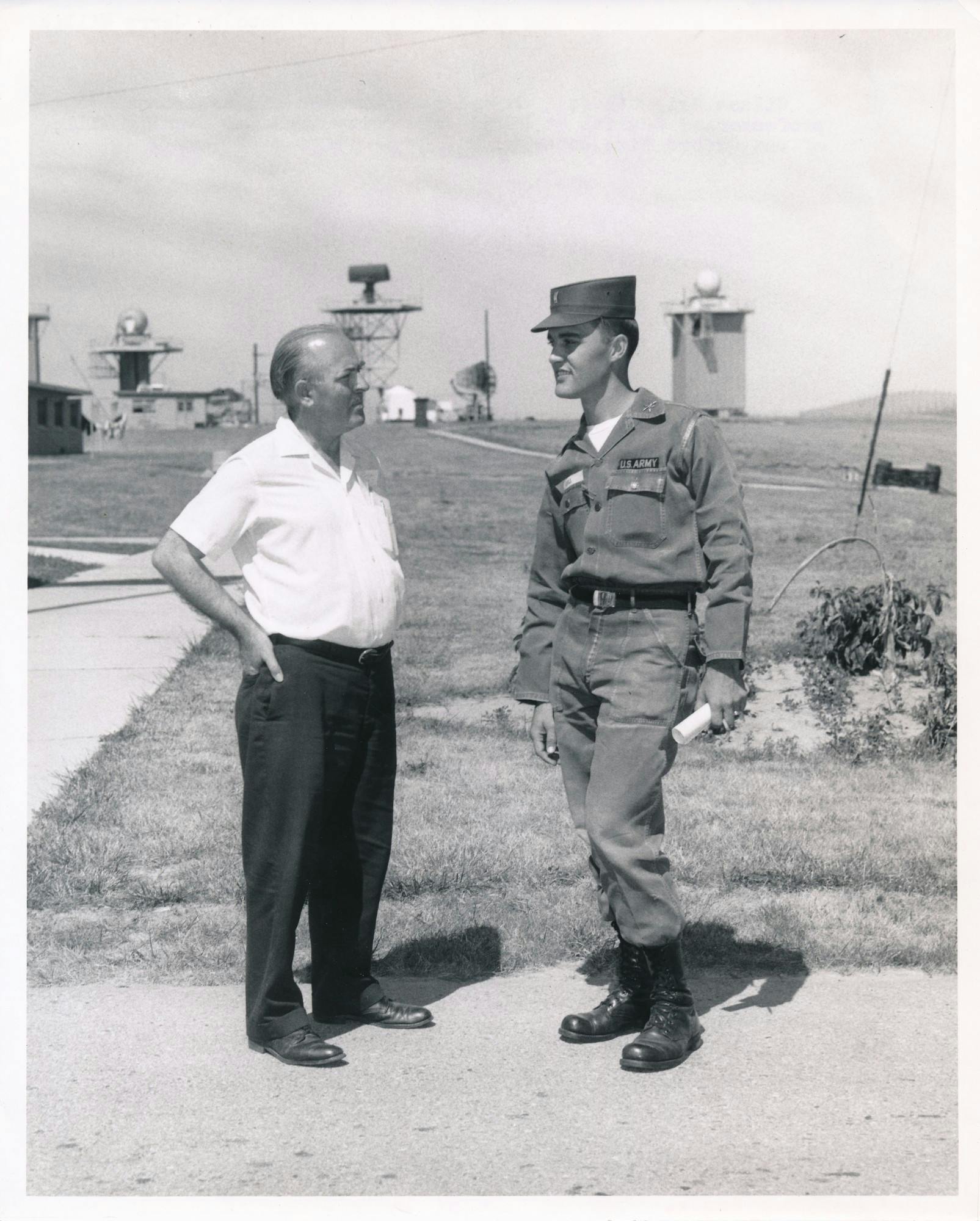

Miami professor Gilson Wright and Lieutenant Stanley Gill talk at the Oxford Nike Missile Base.

All systems go

Though the base was activated in Feb. 1960, its four missile silos, 14 buildings and 14 acres of land wouldn’t be dedicated until May of that year.

The ceremony included the College Corner High School Band, Oxford Mayor Glen Douglas and Captain William Mitchell, the first Commanding Officer of the Oxford Nike Battery.

“The presence of a new defense area in our nation-wide air defense complex is a further step in our ever-growing effectiveness,” the dedication program read, “and is the result of the entire efforts of many people, both military and civilian.”

The base employed 40 men. They raised the four missiles housed there nearly every day.

Shera and her family watched the missiles go up from their now fractured property.

“It didn’t bother us, unless one would have gone off,” Shera said. “My children were all at home at the time. I should have been afraid, I suppose, but I really didn’t pay much attention to them. At first, the kids would be excited. But then they got so used to it they didn’t think anything about it.”

Then, on Monday, Oct. 26, 1962, a speech by President John F. Kennedy.

“Within the past week, unmistakable evidence has established the fact that a series of offensive missile sites is now in preparation on [Cuba],” he told the nation. “The purpose of these bases can be none other than to provide a nuclear strike capability against the Western Hemisphere.”

The Cuban Missile Crisis had started, and disaster seemed imminent.

For Oxford residents and Miami students, Butler County seemed a likely target. The Nike base may have helped keep Cincinnati safe, but it put a target on Oxford’s back with its four underground launching silos and proximity to important railroads.

Local members of the Ohio National Guard and reserve units were called to complete additional training, and the city’s citizens were on high alert.

That Saturday, Miami’s homecoming parade opened with a Hound Dog Missile from the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, sponsored by the university’s Air Force ROTC unit.

On Oct. 28, the crisis ended with USSR President Nikita Khrushchev’s decision to remove all Soviet missiles from Cuba.

Oxford made it through the disaster unscathed.

A base in decline

The U.S. struggles of the 1960s didn’t die down after the Cuban Missile Crisis, but any fears of the Soviet Union targeting the Oxford Nike Missile Base gradually went away.

Hercules Nike missiles were innovative when first designed, but the rapid developments of the Cold War meant they soon became obsolete. Missiles with 75 mile ranges didn’t cut it by the end of the decade: Oxford’s base could have stopped an attack by Soviet aircraft, but it just didn’t stand a chance against intercontinental ballistic missiles with 5,000 mile ranges.

At the end of 1969, the military announced that the base would officially close. By July of 1970, the federal government had declared the land and buildings as surplus property.

Two years later, the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty was signed by the U.S. and the Soviet Union, Richard Nixon resigned and Gene Cernan became the last man to walk on the moon.

The base was briefly in the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare’s possession before the department passed the now-defunct base off to Miami’s Institute of Environmental Services. The university used the land for both ecological studies and storage, hiding away taxidermied animals and art supplies in the buildings.

The Cold War wouldn’t officially end until 1989, leaving Oxford’s decade as a prime military location to the footnotes of southwestern Ohio history.