In February, The Miami Student uncovered almost two dozen accounts of racist imagery in the university's old yearbook publication, Recensio, from 1960 until the publications' end in 2015. Some of the images we found showed incidents of blackface, mock lynchings and students wearing white hoods.

These photos demonstrate that Miami University's complicated relationship with racism has been apparent for decades.

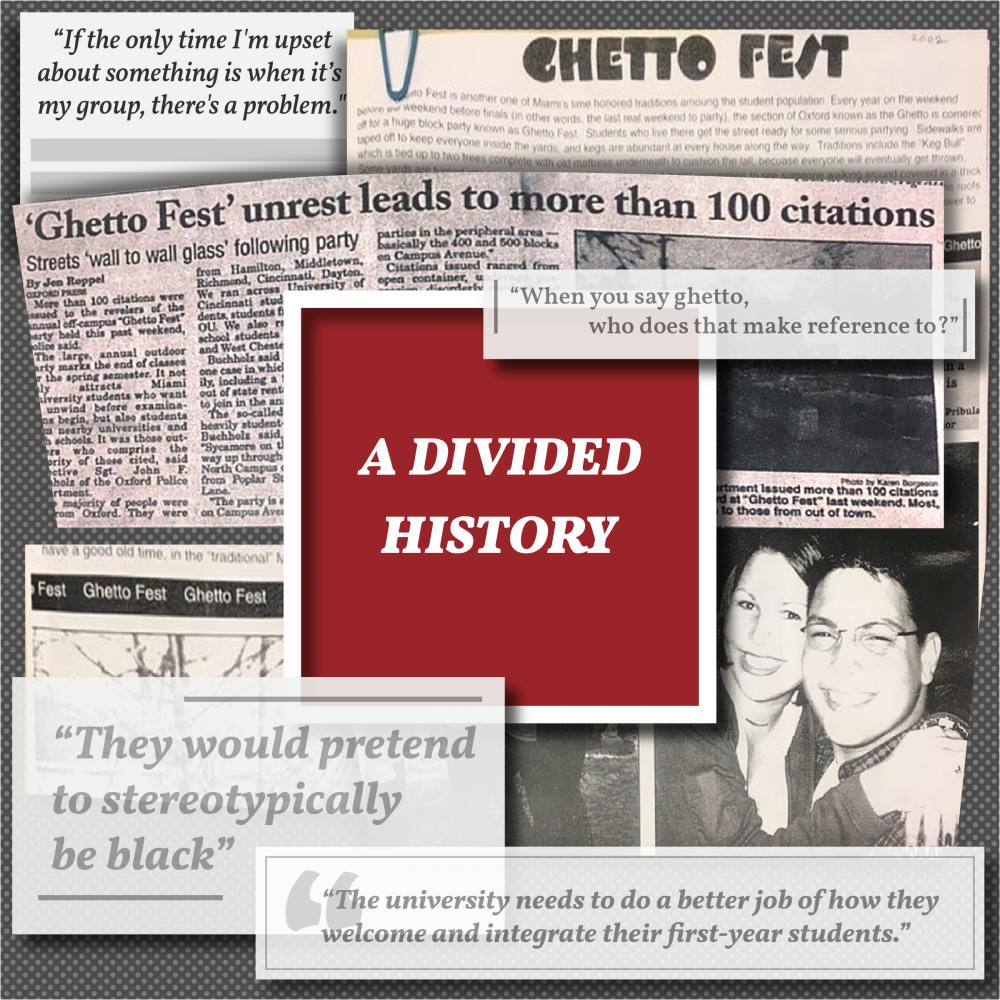

One of the most well-known examples was the formerly annual party, Ghetto Fest. Ghetto Fest was the last big party of the school year that took place in the north end of town, which was a densely populated student housing area. The party spread between Sycamore Street and University Avenue.

Ghetto Fest began in the mid 90s and lasted until 2010, when it ended because students argued that the name of the event was racially insensitive. Although many Miami students participated, it was unaffiliated with the university. Information about the event was spread through word of mouth communication, and the organizer of the event was not documented through city records.

In the Oxford community, Ghetto Fest held different meanings for different groups of people.

John Buchholz, Community Outreach Specialist for the Oxford Police Department (OPD), has worked with OPD for 44 years and assisted in patrolling Ghetto Fest from its birth until its end. He said that in his years of monitoring the event, he never saw anything that would constitute as racist or racially insensitive.

He described Ghetto Fest as a "huge college party."

Participation grew with each year of its existence. In the beginning, it was mostly limited to students, then later evolved to include the participation of families in the Oxford community and individuals from out of town. He recalled even seeing families bring their young children to participate.

Buchholz said the name of the event wasn't meant to be associated with any particular race or ethnicity. From his understanding, the name was based upon the region of town in which Ghetto Fest took place.

"They called it Ghetto Fest only because that area of town was not associated with any race, but was the last part of town to be developed. The conditions up there were not as good as other places in town," Buchholz said.

Rodney Coates, coordinator of Miami's Black World Studies program, was teaching at the university through the duration of Ghetto Fest's existence. He felt that the name of the event had an obvious racial connotation.

"When you say ghetto, who does that make reference to?" Coates said. "This term is not an innocent one in and of itself. It has unique meaning within the U.S. context. You cannot escape that."

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

Chemere Merrida, a '05 Miami graduate, said she and a few other African American students drove by and saw the event up close out of curiosity. She remembered seeing white students dressed up and behaving as their idea of the stereotypical ghetto individual.

"They would play very loud rap music, and they would pretend to stereotypically be black," Merrida said. "They would drink outside, play games, take pictures, pose certain kind of ways. They would participate in things they thought the 'ghetto' was like."

In 2010, after a series of racist and homophobic incidents that took place on and off campus, students took matters into their own hands. There was a town hall meeting conducted to discuss Ghetto Fest and the meaning the word 'ghetto' had to different groups of people.

Soon after, students held a "No More Hate on My Campus" rally. About 250 students gathered on Spring Street outside the Shriver Center protesting against the events that had taken place.

According to previous coverage by The Miami Student, the rally was organized by Miami's LGBTQ+ advocacy group, Spectrum, and other students on campus.

The protest was so effective that Ghetto Fest ceased to exist.

Coates was impressed with the unification among students during that time and their courage to speak out against the events taking place.

"The way students came together against racial lines and condemned [Ghetto Fest]," Coates said. "It was a great moment of protest and counterprotest."

Coates said he believes that the students who organized the event weren't thinking about the meaning of the word "ghetto" or the implications that word had on black students and Oxford residents. . Coates believes these students were just trying to understand an experience they didn't have any attachment to.

He compares these students' interpretation of the ghetto, to the audience who saw the Oscar nominated film 'Black Panther' and assumed they understood what it mean to be African.

"I don't think they planned to do this. I don't think there was any thought of this word." Coates said. "It's very much like me watching Wakanda and having an 'African experience.' The film was so far from Africa that it wasn't even funny, but so many experienced Africa through the eyes of a cartoon. It's the same kind of thing. This [Ghetto Fest] has no real connection to reality. They were having a Wakanda experience without any experience of what the reality of a ghetto is."

Buchholz acknowledged there were a series of racial and homophobic incidents that preceded the "No More Hate on My Campus" rally and feels that Oxford and Miami have come a long way in their promoting social awareness about these systemic problems..

"There were a series of racial events in Oxford not associated with Ghetto Fest," Buchholz said. "Now, people are a lot more attentive and in-tune with racial and homophobic type of things, whereas back then, I think that was when Oxford and Miami were just beginning to wake up to these events."

Like many universities, Miami has historically had low minority enrollment. As of Oct. 15, 2017, there were only 1,034 African American students enrolled across Miami's main and regional campuses. This is only 4.2 percent of the total enrollment that year.

In an attempt to recruit more students of color, Miami has implemented initiatives such as the Bridges Program, which reaches out to students of color and those who are from low-income backgrounds.

Merrida knew of racial tensions on Miami's campus as a prospective student. Her senior year of high school, Miami's mascot was changed from the Redskins to the Redhawks, and she recalled many people were displeased. She said the change "brought all the racists out."

Through experience and by attending Miami while Ghetto Fest was held every year, she was not surprised to hear The Student had uncovered the racist images in Recensio.

"We're in the Midwest in a very conservative university, in a very conservative county, of a very conservative state," Merrida said. "Nothing like that can really shock me. What does surprise me is that they had the gall to flat-out take pictures and publish them as if it weren't wrong."

Coates feels that people should be aware and not only respond to acts of racism when it directly affect them.

"If the only time I'm upset about something is when it's my group, there's a problem," Coates said. " If I am indeed concerned with social justice, then that means that I understand that there is this rainbow of people and identities that I need to be concerned with."

Merrida said she enjoyed Miami's social scene, but feels Miami must put in more effort to make students of color comfortable.

"The university needs to do a better job of how they welcome and integrate their first-year students," Merrida said. "The majority of students at that school will always be white; they will always be of a certain class and always be of a certain financial background. So, how do you make these students who come in [and] have experienced a privileged life for so long, how do you shape them to be more aware?"