"Here you go."

"There you are."

"No, thank you."

These were the three-word phrases my brother Jackson and I had been practicing for around 15 minutes at the church entrance. We knew we sounded like perfect children, the ones other children despise. But, since our mother was the chieftain of the 5 p.m. mass at our parish -- which really meant using any of her nine children to fill in the positions needed -- we gladly accepted the simple task of handing out song sheets before the liturgy.

At one point, a rushed family of three rejected my song sheet, recoiling as if it were an old gym shoe.

"What's up their butt?" I asked Jackson. "I mean, who can't be polite enough to accept a frickin' piece of paper? What, are they some busy lawyers who have no time for our petty requests?"

Jackson, a professional at offering song sheets, having built up a particular set of reaching arm muscles over two years, told me to keep on keeping on.

"Don't worry, they always ignore us."

To compensate for being ignored before mass, I spent most of the actual service in the back of the church with my older brother Tucker and his six-month-old, a fat ball of smiles named Gus.

"Gus is the best," I was telling Tucker. "Anyone who can get away with putting his mouth on everything near his face has my vote." This, after Gus had grabbed hold of my hair, stuffing it into his mouth where he slobbers most things to oblivion.

"What if he never stops?" Tucker asked.

"You mean, shoving people's faces into his mouth?" I said.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

"Well, yeah, what if he's 30 and he still greets people by drooling on their noses?"

This was a fantastic image, especially for a church daydream. In my head, I pictured a lanky, 6-foot-tall, bald-headed Gus barely able to stand on his two feet, stumbling towards his houseguest with the intent of bracing his fall by widening his jaw. People would talk, no doubt. He wouldn't be taken so seriously but, then again, neither is his father, the one who conjured this image in the first place.

"Graham!" my mom said in a hushed yell, rousing me from my dream. She motioned toward the front of the church, where all the Eucharistic ministers -- that is, those who disperse the Body of Christ -- were gathering.

As was custom, I took my mom's place, assuming what seemed like a Battleship coordinate "3-B" (position three, bread). Passing through the aisles, I began to consider how I'd spend my time giving the Eucharist.

I had been supplying the crowds with their Bodies of Christ for all of three years, being bowed to at least a few thousand times. For most of those bows, I simply waited for the head to pop up so I could give the host, almost thoughtlessly. While standing there, I would liken the process to picking popped kernels out of a bowl of popcorn, one by one.

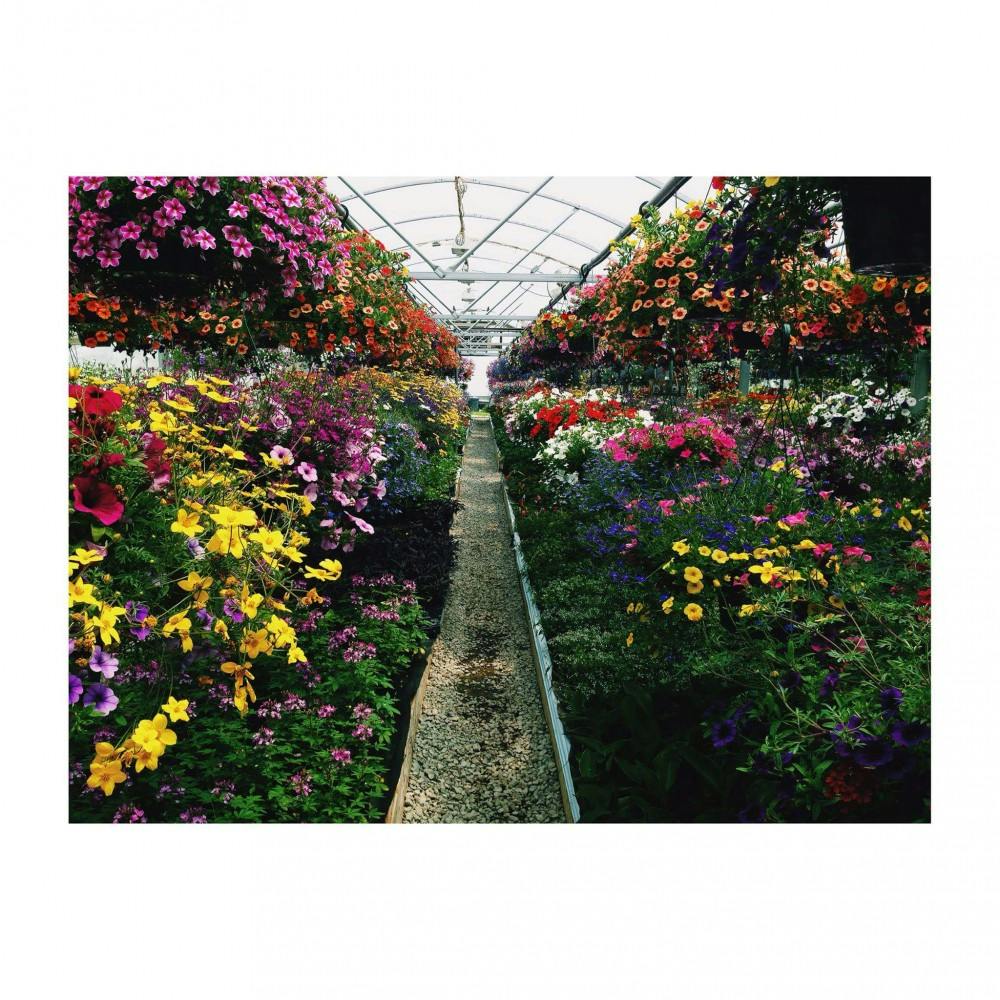

This is how I spent many a day when I working last summer on my girlfriend Susie's flower farm. That is, I daydreamt through monotonous tasks like watering, weed whacking, suffocating cabbage-craving caterpillars and, on one occasion, scattering slabs of asphalt that would later be called a driveway. "Gathering wool" in these instances was, for the most part, safe to do, as the worst case scenario saw me watering the same impatien -- a flower about the size of an 80-year-old's ear -- for four minutes, effectively drowning it and, for good measure, drowning it several more times.

At this point, things get a little foggy. I remember her as an older lady asking questions about our tomato plants. What tomato plants? Oh, the ones right at my quivering feet, the ones we were selling. Right. In a mini-miracle, I sold the lady her tomatoes. Only, I recall double-checking after she left to learn that yes, oh shit, I had also sold her some hot pepper plants.

After that, I did not return to the market. I asked Susie's mother, my boss, about a comeback possibility, a chance to right my wrongs. At this, she laughed like she always did when she felt even the least bit uncomfortable.

"Oh, we've got it covered, you stay here at the farm and work, that's where we need you," she pleaded.

I agreed, but out of fear that I might return, I felt an obligation to study the plants, to differentiate between tomato stalk and pepper stalk. I'd have the chance over the course of many 6-hour days spent watering.

Eventually, I came to see them as my imaginary family, me the adoptive parent of a few hundred, well-behaved plants -- not that I was the most benevolent father. Some days, I would stare with contempt at an Echinacea -- this tall and uncoordinated flower whose focus point was a pathetic excuse for what people call a cone. Because I could, I would threaten to dehydrate him until his flimsy stem drooped with melancholy.

"Fine, what do I care? All I do is stand here anyway," I heard the flower saying.

Then, after scaring myself at how power crazy I could get, I would douse the poor thing and repent by listening to Tchaikovsky's Waltz of the Flowers on repeat, sure that some transcendent magic would force the horizontal mess back to life and, if I was lucky, force the flower to dance.

Despite my shortcomings with the flowers, I continued the journey of adding to my lexicon funny words I would have once thought to be the names of pop artists or antiquated board games, words like azalea and begonia, zinnia and ranunculus or, my personal favorite, the portulaca, assuredly a Spaniard's battle cry at some point in history.

That day at the church, I found myself among throngs of Communion-seekers, marching like those Spaniard soldiers might have, as I approached the altar to distribute the hosts. My train of thought derailed as I took my spot near the side aisle pews, bowl of Jesus hosts in hand. Like I had with the flowers, I started to take note of the individuals, generating certain genus based on how the host was received.

There was the customary approach -- bow, present pancake hands, take and go. There was the apathetic approach, whereby the recipient would nod his head like someone fighting a nap and lift their hands, half-balled so that I had to force the host into the lazy palm. There were the overly eager ones, the "Oh, I'm in church? Sweet, a snack!" ones, and, of course, those who didn't trust their arthritic hands and so stuck out their tongues instead.

Again, I was reminded of Gus in these situations, only, instead of finding it cute, I was rather amused at how similar placing the host on an outstretched tongue was to inserting a crisp dollar bill into a vending machine. I didn't get any snacks, but the wry smiles of the elderly that followed were enough for me.

Then came the tag team, the married couple who bowed simultaneously and, I don't know, maybe they expected me to present two Bodies of Christ at the same time which, of course, is asking for disaster. "We are one body," they seemed to say. I took my time delivering the mini Christs and, just as the couple walked away, I recognized them as the ones who had ignored my song sheet.

Although they had come across as snooty, I couldn't help but notice their solidarity in all actions. It was as if they did everything as a team, even in their condescension. They added complexity to the heterogeneous clump of churchgoers, a group both different and the same -- they consisted of others like this couple, but also more liver-spotted limpers, all united in their open mouths, their Gus mouths.

"There you are," I whispered. "There you are."