KAYFORD MOUNTAIN, West Virginia. - Here, Junior Walk lives off the land. He travels the same trails his grandfather once did. His great-grandparents are buried up here. He doesn't bother with a cellphone - where he lives, it won't get reception - and he loves his guns. But coal mining, he says, is threatening that existence.

What's more, mining - and, in the last 25 years, a particularly nasty brand called "mountaintop removal" mining - is desecrating Appalachia, its environment and its people.

[video width="640" height="360" mp4="http://miamistudent.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/FINALVIDEO-FOR-KAYFORD_CLIPCHAMP_360p.mp4"][/video]

A brief explanation of Mountaintop Removal

The landscape, however, will never recover.

Much of the coal that powers Miami University's campus and the Oxford, Ohio-area is extracted from mines like those that surround Kayford Mountain.

The state has long been a hub for coal mining and, in Appalachia, almost nobody is unaffected by the industry. Junior is 25 years old. Coal companies ramped up mountaintop removal mining in the mid '90s, when he was a kid.

"I've watched them tear it all up," he says.

On the West Virginian horizon, where the mountains used to dip and soar, the contours of many are now flat. This is what Junior wants the world to see. And, on a damp November weekend, it's what he says he wants to show us, a couple journalists visiting from Ohio. But he also wants to show us his culture.

"You boys wanna eat some squirrel tonight?" he says, his way of greeting us.

[media-credit name="Kyle Hayden" align="alignright" width="900"] [/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

Junior Walk, part time volunteer at Coal River Mountain Watch, rolls a cigarette as he looks at the mines surrounding Kayford Mountain

"I don't know, it's meat meat," he says.

Junior has long hair and a bushy beard. He deftly rolls his own cigarettes. And, of course, he makes a mean squirrel stew.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

"Squirrel season comes in the middle of September," he says. "I'd say it's a staple meal in the fall."

He's an avid hunter, but not for the sport of it - "those people are dicks," he says. Whatever he shoots, he eats.

"The way I was raised is, whenever you kill an animal, you're gonna eat that animal," he says. "The culture here in Appalachia is that of self-reliance, of being able to take care of you and yours."

It's this lifestyle that Junior says coal companies are endangering.

"They're not only destroying our water and land, but also stripping away our culture," he says. "There's not that much habitat left for squirrel or deer, or wildlife in general."

Junior, like most who live in coal country, comes from a lineage of miners. His father and grandfather worked in the mines. He was born and raised near Whitesville, on the banks of Coal River. Junior felt the effects of the coal industry before he ever saw a mountaintop removal mine.

"Our water was really bad when I was a kid," he says.

He remembers turning on the tap in his parents' house and watching red, foul-smelling water drip out. This happened after a mining blast cracked the aquifer near his house and allowed coal slurry - the toxic, sludge-like byproduct of coal washing - to seep into his family's well.

His water stayed contaminated for several more years.

By the time he graduated from high school, Junior was ready to leave. He applied and was accepted to a couple colleges before he realized he didn't have the money to pay for it. So he did what so many of his town's high school graduates do: he went to work for a coal company.

At 17 years old, Junior began working at the same coal plant his father worked at, doing general maintenance. Some days it wasn't so bad - he'd cut the grass. But others, he'd find himself in the basement of the plant, waist deep in coal slurry, spraying the sludge with a pressure hose to move it through grates in the floor to a storage impoundment.

"No respirator, no goggles, fumes coming up and hitting you in the face," he says. "I quickly realized that if I kept doing that, I was going to die."

He only worked there for six months. But it didn't take long for Junior to start working for a coal company again. After a couple odd jobs and a stint living out of his car, Junior began working as a security guard on a mine site.

He immediately felt out of place.

"I felt miserable about it," he says. "The more I thought about it, the more I was like, 'I don't want to be a goddam cog in their machine of poisoning people.'"

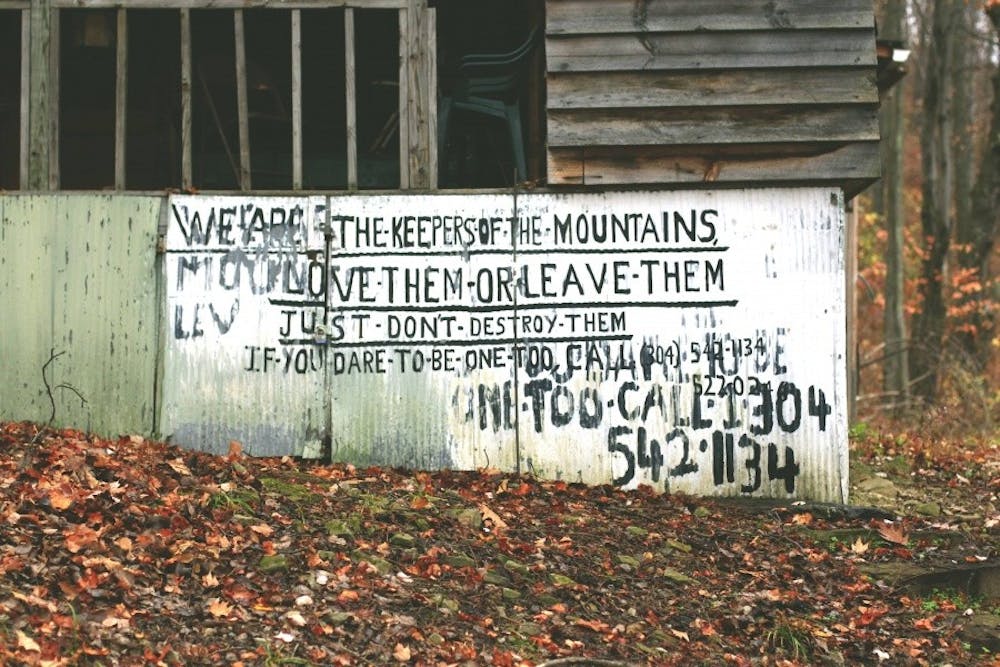

After he left that job, Junior became a fulltime activist and got involved with several prominent local environmental groups. Among others, Junior worked with two late, world-renowned activists, Larry Gibson, whose family has Kayford Mountain in a land trust and who started the Keeper of the Mountains Foundation, and Judy Bonds, the former executive director of Coal River Mountain Watch, where Junior now volunteers.

Since then, he has been fighting coal companies head-on. He lobbies the state and federal government and speaks at colleges across the country to raise awareness. He's also organized demonstrations and sit-ins.

"If hippies wanna find themselves a big piece of yellow equipment to chain themselves to, I will point it out to them," he says. "I'll hand them the lock."

He won the Brower Youth Award, an environmental prize, for his actions and has been to jail twice, arrested during protests.

However, his outspoken views are dangerous ones to have here in southern West Virginia. When Junior first started doing anti-coal work, his father, who still worked for a coal company at the time, had to kick Junior out of the house.

"He didn't want to, but he had to because he knew if I was doing this work, and I was living under his roof, he would've lost his job in a heartbeat," Junior says.

But there are others, mostly people who work in the coal industry, who genuinely wish him harm - groups with names like Citizens for Coal and Coal Miners Militia, who don't like what Junior's doing. They want the coal jobs to stay.

"They're the type of people who're the reason I carry a pistol everywhere I go," Junior says.

[media-credit id=6408 align="alignleft" width="900"] [/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

Two Miami Student reporters join Junior Walk as he surveys the destruction caused by mountaintop removal.

"It's the fact that I've been at this for as long as I have," he says. "I haven't calmed down on it at all."

Environmentalists like Junior and those who oppose him represent two extremes here. The majority of people, though, are somewhere in the middle - they may not like the coal companies, but they rely on them for paychecks.

"They're just trying to survive," says Michele Morrone, a professor and coordinator of environmental health science at Ohio University. "Coal has made that possible."

Morrone, who has worked all her professional life in Appalachia, writing about and researching public health, says the area's focus on coal has bred an economic reliance on the industry.

"The lack of diversifying and educating people has placed a lot of families in a trap," she says.

That's because coal is quickly falling out of favor, usurped in many places by natural gas. As coal companies lay people off, communities here are suffering. Counties in Appalachia are among the nation's poorest and drug addiction is rampant.

"There are no jobs here," says Adam Hall, a full-time volunteer for Coal River Mountain Watch. "If you work in a gas station, you are a reputable person here, right? You have something. That's not the kind of place that I think people should live in."

Adam says that, in order for the region to recover, communities must realize that the coal industry's days are numbered.

"You know, coal gave us this, but coal also left us that," he says. "They ain't coming back again. There's no boom coming. It's just a bust and a bust and a bust now."

Adam is an idealist. He's confident Appalachia will again prosper. Junior is less so. He says he doesn't have much hope for the future.

"I'm a pessimist," Junior says.

But that won't stop him from fighting.

"What else are you going to do, you know?" he says. "The fact of the matter is, even if they do all the mining they do before they leave outta here, you still gotta raise hell about it, because people gotta know about it. If people don't know about it, it's like it never fuckin' happened."

Much of the world still runs on coal, yet few people in places like Oxford, Ohio or at Miami University see the effects the industry has at the point of extraction. Junior and Adam have made it their lives' work to make people aware.

"Be mindful, just be mindful," Adam says, speaking to us like he's talking to the rest of the world. "Every time you touch that light switch, that's not free. And it's not just your money that pays for it. There is water that gets poisoned for it. There is air that gets poisoned for it. There are people who die for it."